When Law Enforcement Comes Knocking, Companies Can Start Fighting

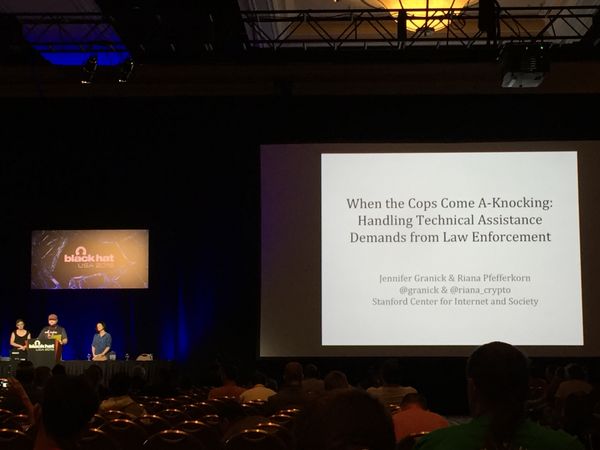

Debating whether there”s any legislation that may allow the government to force companies into building backdoors, decrypt on-device data, hand over decryption keys or use any company”s software for surveillance purposes, Jennifer Granick and Riana Pfefferkorn from the Stanford Center for Internet and Society have taken the stage at Black Hat 2016, Las Vegas, and shared some interesting legal insights.

Touching on cases like the Snowden or the Lavabit incidents, the duo strongly emphasized that companies should start asking themselves a couple of questions before law enforcement actually comes knocking at their door. Knowing what they collect, how they store it, for how long, why, what can it access, does it encrypt data and where are keys stored – are only a few of them.

While both the Wiretap Act and CALEA (Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act) may have been designed to increase the surveillance capabilities of law enforcement agencies, Granick argued that companies shouldn”t necessarily give in to law enforcement”s pressure, without a Department of Justice search warrant in conjunction with AWA (All Writs Act) writ.

Requests are not orders, said Jennifer Granick, the Director of Civil Liberties at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society. Companies should exercise their independent judgement.

Because there”s currently no legal precedent, it is unknown if from a legal standpoint law enforcement can force companies to write new software, turn on the microphone or camera, hand over encryption keys, or decrypt data by invoking CALEA or AWA. However, even if a company has been served with a search warrant, they can still file an appeal and potentially change the decision.

Referencing the San Bernardino case of Apple versus the FBI – where the AWA was levered in trying to get Apple to create new software that can decrypt the terrorist”s phone – the company was able to fight off the FBI”s request by getting a different ruling from a second judge. However, it unclear whether or not Apple should have complied, according to Pfefferkorn.

“Is it necessary for Apple to help out?” said Riana Pfefferkorn, the Cryptography Fellow at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society. “We don”t really know.”

Even in the Lavabit incident in which the FBI wanted to get the company”s private keys to decrypt Snowden”s emails, the duo concluded that historically very few companies have actually been obliged to comply with their demands.

As for law enforcement requesting backdoors into systems, non-CALEA entities are in no way obliged to be designed in a “surveillance friendly” way, nor are they obliged to “ensure decyptability if they do not both provide the means and have the keys”

The session”s takeaways were that requests are not orders and that orders don”t necessarily mean that it”s the law. Companies should exercise their own independent judgement and embrace encryption.

They also advised that companies should push back where possible – especially if they get an overwhelming demand of requests – and talk about the demands they get, as to make sure that they don”t violate the individual”s right to privacy.

tags

Author

Liviu Arsene is the proud owner of the secret to the fountain of never-ending energy. That's what's been helping him work his everything off as a passionate tech news editor for the past few years.

View all postsRight now Top posts

Cybercriminals Use Fake Leonardo DiCaprio Film Torrent to Spread Agent Tesla Malware

December 11, 2025

Genshin Impact Scam Alert: The Most Common Tricks Used Against Players

December 05, 2025

How Kids Get Automatically Added Into WhatsApp Groups with Horrific Imagery Without Consent

November 24, 2025

Scammers Exploit Hype Around Starbucks Bearista Cup to Steal Data and Money, Bitdefender Antispam Lab Warns

November 18, 2025

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

You might also like

Bookmarks