Stuxnet's Oldest Component Solves the Flamer Puzzle

As we previously stated in our first blog post, there is a component that may link Stuxnet to Flame. This component called atmpsvcn.ocx, was a piece of malware that was detected as a generic sample of Stuxnet. We discovered it while attempting to isolate other Flamer components by looking for similarities between the currently known components and other e-threats. We stumbled upon two highly similar files that feature common C++ classes and that have the list of various operating systems encoded in the same manner.

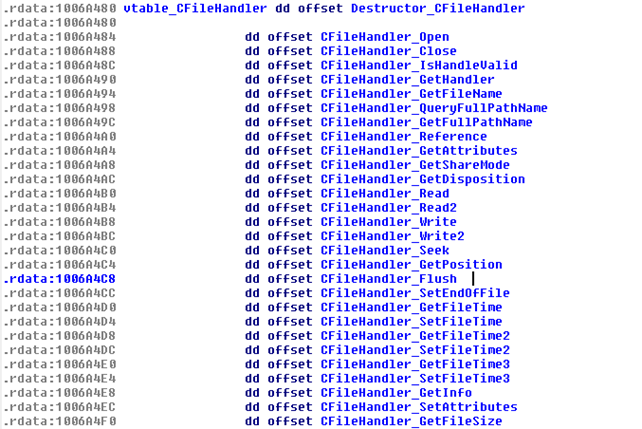

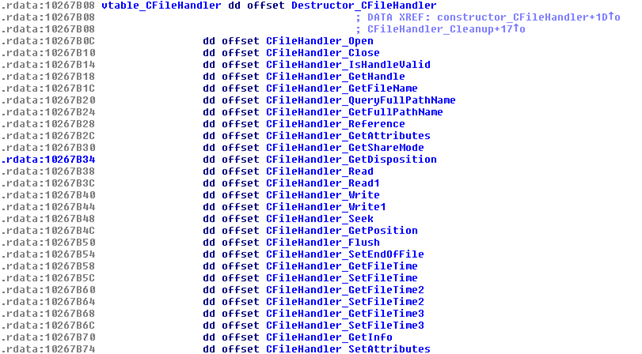

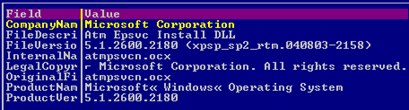

Fig. 1 : C++ classes in atmpsvcn.ocx (Stuxnet)

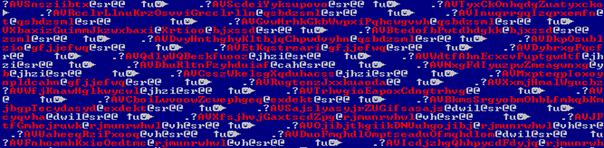

Fig. 2: Classes in mssecmgr.ocx (Flame)

The full story comes after the break.

Stuxnet

As mentioned before, atmpsvcn.ocx was believed to belong to Stuxnet: more to the point, its MD5 hash (b4429d77586798064b56b0099f0ccd49) was detected in a Stuxnet dropper. This irrefutably places it as a Stuxnet component. It is common knowledge that Stuxnet used quite an array of droppers, and one of the oldest such droppers, dated from 2009, also contains the atmpsvcn.ocx component. Inside the dropper, we identified a resource encrypted using XOR 255 (0xFF) that is 520.192 bytes large and has the same hash: b65f8e25fb1f24ad166c24b69fa600a8.

This concludes the first part of the demonstration. There is no doubt about it being a Stuxnet component, but today’s demonstration will shed new light on how it fits in the Flamer puzzle.

Flame

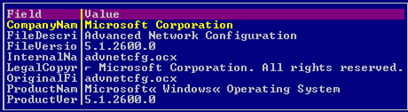

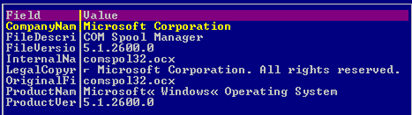

Before proceeding any further, let’s stop to have a brief look at some particularities of Flame components compared to atmpsvcn.ocx. Here is how the Flame components look as far as the VersionInfo section is concerned:

Fig. 3: The advnetcfg.ocx component (Flame)

Fig. 4: The comspol32.ocx component (Flame)

Fig. 5: The atmpsvcn.ocx component (Stuxnet)

We have two different Flame components and the atmpsvcn component, and all of these three binaries look like they are coming from Microsoft. Also, please notice the .ocx extension. Going on with the information, a closer look inside the structure of binaries of the components belonging to Flame and atmpsvcn.ocx would reveal the following:

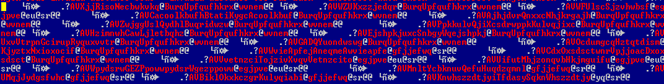

The C++ class names from RTTI structures (Run-time type information) are randomized:

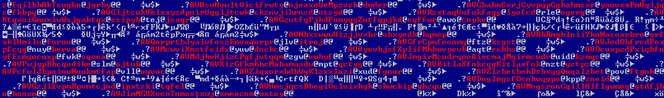

Fig. 6: Class names for msglu32.ocx Flame component (Flame)

Fig. 7: Class names for mssecmgr.ocx main Flame component (Flame)

Fig. 8: Class names for atmpsvcn.ocx Stuxnet component.

All class names are randomized, so it wouldn’t be possible to find the real names the programmer gave them. We think that this ‘randomization’ is actually the result of a function that takes the real name of the function and then it scrambles it beyond recognition. We have found the same scrambled names in different components, such as atmpsvcn.ocx, msglu32.ocx and comspol32.ocx.

For example:

AVInuqrrgqIzqrxemfn@qsbdzsml@sr@@

AVFqpgtZkqrTzylfxafQpgtzkqrt@qsbdzsml@sr@@

AVGvwHrhkGkbWwpxiPqhcwgvwh@qsbdzsml@sr@@

AVTohkuixgRflZavycpWtohkuIxgrflzav@qsbdzsml@sr@@

String decryption algorithm

The Stuxnet components use the same encryption algorithm for the strings they contain. This is visible in components such as atmpsvcn.ocx, s7otbxdx.dll and mssecmgr.ocx, which are documented below.

- in the case of atmpsvcn.ocx and s7otbxdx.dll (the Siemens SCADA proxy DLL), the decryption algorithm looks like this:

for (i=0; i < strlen(s); i++)

{

sum = (0xB + s[i]) * (0x11 + s[i]);

s[i] -= (sum >> 0x18) ^ (sum >> 0x10) ^ (sum >> 0x8) ^ sum;

}

- in the case of the main Flame component (mssecmgr.ocx) it looks like this:

for (i=0; i < strlen(s); i++)

{

sum = (0xB + s[i]) * (0x17 + s[i]);

s[i] -= (sum >> 0x18) ^ (sum >> 0x10) ^ (sum >> 0x8) ^ sum;

}

We can clearly see that the only difference is a constant!

This makes us believe that Flame is linked to Stuxnet through a component they share: atmpsvcn.ocx. The components in Stuxnet and the binary file in Flame use the same string decryption algorithm. But let’s go further with an anatomy of the atmpsvcn.ocx component.

The memory stick infector

The USB storage infector (atmpsvcn) exports a single function only, called “_0”, and which takes three parameters: a drive letter, a buffer containing the payload and the length of the payload-buffer.

It checks the operating system’s version, and if it’s Vista or above, it stops the infection process. The code that performs the check is very interesting, as it isn’t aware of Windows 7, which is factual proof that it was written before 2009, probably in 2008.

It then creates two files on the memory stick: autorun.inf and ~XTRVWP.dat. While ~XTRVWP.dat plays the role of the payload passed as parameter, the autorun.inf file is actually a PE file that comes embedded with atmpsvcn.ocx. These two files are created on the disk, and then the FAT directory entry is modified so it becoms invisible to the user.

FAT directory entry exploitation

One particularity of Flame is that it is exploiting a weakness in the FAT file-system, which allows it to hide its files. By hiding, we mean that these files won’t be visible if they get enumerated via the FindFirst/FindNext API. Flame achieves this by performing raw modification on the directory entries in the FAT file-system. Most memory sticks are using the FAT file-system, and Flame, so far, exploited this to hide its database.

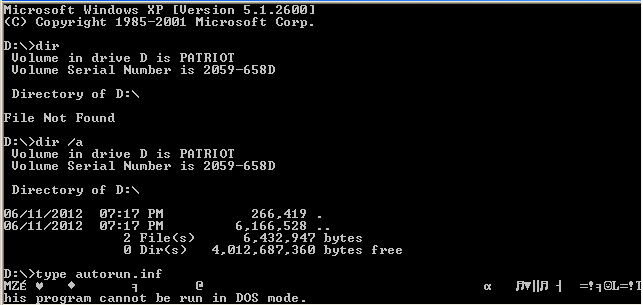

Fig. 9: Hiding files from the human user

This time, we have two files: one of them has the long name ‘.’ and the short name autorun.inf, while the other one has the long name ‘..’ and the short name ~XTRVWP.DAT as you can see in image above. (PATRIOT is our memory-stick volume label). File names are very-well chosen, as the dot files won’t be visible.

Back in the DOS era, a file could be named using maximum 8 charachers + three others as extension. As Windows gained ground, this limitation disapepared with the implementation of long names.

Of course, these files can be accessed using their short-names, as you can see in the snapshot below:

Fig. 10: files can be accessed using their short names

~XTRVWP.DAT contains the payload (The Flame or Stuxnet droppers), especially the one that can be found in Stuxnet. This one is an autorun.inf file that is also a PE file whose file overlay contains the actual autorun.inf:

[autorun]

objectDescriptor={B315537-63AB-9512-99A9-2F4677235A44}

shell\Menu\command=.\AUTORUN.INF

shell\Menu=@%windir%\system32\shell32.dll,-8496

shell=Menu

UseAutoPLAY=0

Windows will parse the exe file until it finds the [autorun] section so autorun.inf plays two roles: it acts both as an infector and as an infection trigger (a fully-fledged autorun.inf file). As we already mentioned, this approach was also used in Stuxnet, but got replaced with the .lnk vulnerability (CVE-2010-2568). We won’t dig too deep into this, as it was well documented in the past.

The infector (autorun.inf)

Initially, the infector reads the payload (~XTRVWP.DAT) played by the hidden file ‘..’ on the memory stick. Since it needs to escalate its privileges to Administrator in order to do the dirty work from a trustworthy process, it exploits a vulnerability that allows it to execute its code in kernel mode.

Kernel mode exploitation

Fully patched copies of Windows XP are not vulnerable to this exploit anymore. However, a computer running a non-patched distribution of Windows XP SP3 is vulnerable. The OS version is programmatically checked, along with the installed service pack. It is also worth mentioning that this vulnerability was fully patched in late 2009. The flaw resides in a win32k.sys driver and is triggered by the usage of two undocumented API calls to NtUserRegisterClassExWow and NtUserMessageCall.

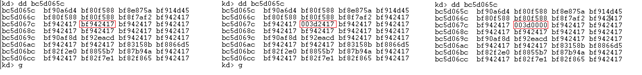

With the help of NtUserRegisterClassExWow, the technique overwrites the handler for message 0x401 (the first user-defined message) in two steps, each call overwriting a WORD:

Fig. 11: The two calls overwrite a WORD each

The code from this address will be called using NtUserMessageCall, and it runs in kernel mode, which grants it full control over the system.

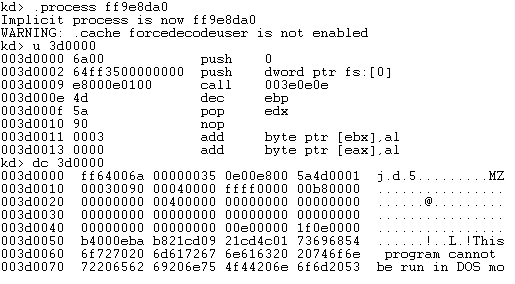

If we dump the code from the given address (0x3d0000) we see that it contains a call to the code that injects the payload into winlogon.exe; right after the call, there is the payload.

Fig. 12: Code dump

Next, the kernel-mode code continues its execution in csrss.exe, from where it creates a temporary file (%temp%\snsm7551.tmp) and sleeps for a couple of minutes. After this, it injects code into winlogon.exe, which will subsequently execute the payload.

Payload execution

This is another interesting part that confirms the link between Flame and Stuxnet:

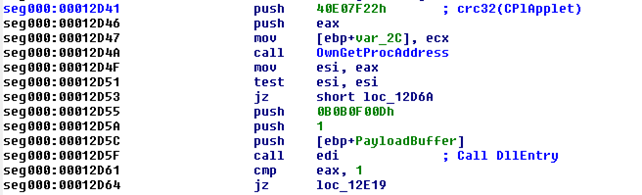

Fig. 13: Function that searches for export CPlApplet (injected code from winlogon.exe)

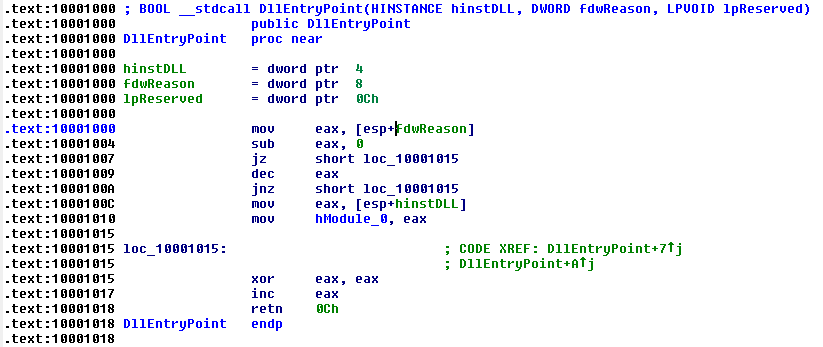

It has a function that searches for the export CPlApplet (via CRC32) of the Payload (both Flame and Stuxnet have this export) and calls the entry point of the payload with a strange value for the parameter lpReserved: B0B0F00D. Stuxnet’s main DLL file also contains an export named CPlApplet, and its DllMain looks like:

Fig. 14: DllMain of Stuxnet

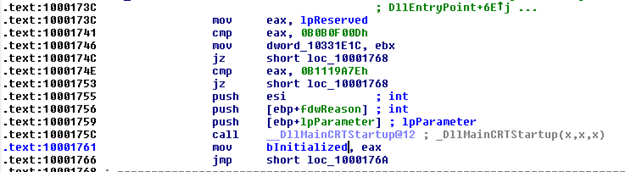

We can see that it does not verify this parameter; however a closer look inside the main Flame dropper and its DllMain reveals the following:

Fig. 15: DllMain of FLAME mssecmgr.ocx

What does this mean? So we have the Flame dropper that verifies the magic value provided by atmpsvcn.ocx and the Stuxnet dropper that doesn’t. Therefore atmpsvcn.ocx is more related to Flame than to Stuxnet, but we surely have this component in an old Stuxnet dropper. It looks like Flame is older than Stuxnet, is part of the Flame project and was shared with the Stuxnet project.

Next, the CPlApplet export is called and passed to the following structure:

typedef struct _CPLApplet_PARAM

{

PVOID ImageBase; // the address of the memory aligned and relocated payload

DWORD dwTempFilePathLength; // the length in characters of the name of the temporay file

PWCHAR szTempFilePath; // the path of the temporary file created before

DWORD dwFileSize; // the original size of the payload

PVOID Payload; // pointer to the copy of the payload

DWORD dwImageSize; // size of the memory aligned payload

PVOID EntryPoint; // Address of EntryPoint in memory

}CPLApplet_PARAM, *PCPL_Applet_Param;

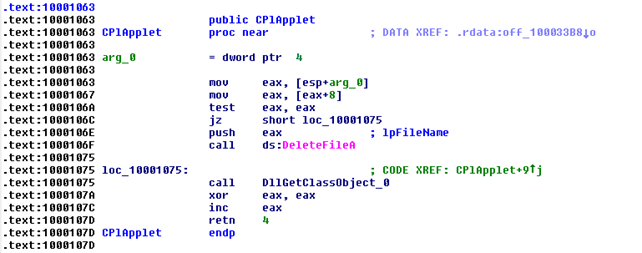

The CPlApplet export of Stuxnet only does the following:

Fig. 16: CPLApplet Export in Stuxnet

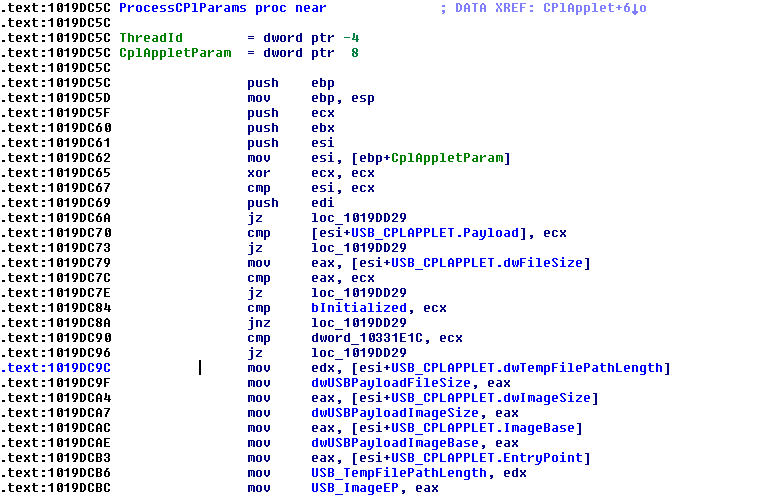

It does not verify the rest of the parameters, it only deletes the temporary file. Flame however uses all the parameters:

Fig. 17: CPLApplet Export in Flame

Also, it is very important to mention that antorun.inf and ~XTRVWP.dat are deleted from the memory stick after successful execution! This way, the spreading is kept under control, which leads us to believe that this kind of infection only occurred on demand and it was targeted at a couple of systems only.

We also managed to successfully infect a memory stick using atmpsvcn.ocx and Flame as a payload. Successful infection revealed the database we were talking in the previous blog post on the memory stick.

These findings are enough of a proof that there is a strong link between Stuxnet and Flame. The missing link, the atmpsvcn.ocx was designed for Flame and also used in Stuxnet. All this time, the truth was right in plain sight: a Flame component detected as Stuxnet and labeled by the antimalware industry as a known threat.

tags

Author

Right now Top posts

Infected Minecraft Mods Lead to Multi-Stage, Multi-Platform Infostealer Malware

June 08, 2023

Vulnerabilities identified in Amazon Fire TV Stick, Insignia FireOS TV Series

May 02, 2023

EyeSpy - Iranian Spyware Delivered in VPN Installers

January 11, 2023

Bitdefender Partnership with Law Enforcement Yields MegaCortex Decryptor

January 05, 2023

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

You might also like

Bookmarks